Winter 2019 NUMBER 143

Focus on ASW

Also in this Issue:

The Case for Integrating the Tactical Support Unit (TSU) into Fleet Training What About Fido? MEDEVAC in the Gulf MEDEVAC OIR Photo Contest Winners

Focus on Anti-Submarine Warfare

FOCUS: ASW

LT Pederson ‘s photo“Dropping a Gift”.

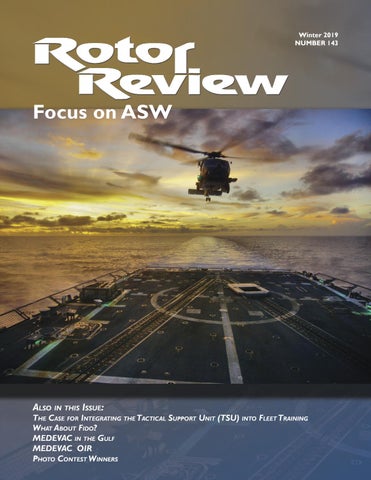

Winter 2019 ISSUE 143 HSM-51’s Warlord 11 comes in to land on USS Mustin (DDG-89) while on routine patrol in the South China Sea in the SEVENTH Fleet area of responsibility. Photo taken by LT Conrad Schmidt, USN. Rotor Review (ISSN: 1085-9683) is published quar terly by the Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. (NHA), a California nonprofit 501(c)(6) corporation. NHA is located in Building 654, Rogers Road, NASNI, San Diego, CA 92135. Views expressed in Rotor Review are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of NHA or United States Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard. Rotor Review is printed in the USA. Periodical rate postage is paid at San Diego, CA. Subscription to Rotor Review is included in the NHA or corporate membership fee. A current corporation annual report, prepared in accordance with Section 8321 of the California Corporation Code, is available on the NHA website at www. navalhelicopterassn.org. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Naval Helicopter Association, P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578. Rotor Review is intended to support the goals of the association, provide a forum for discussion and exchange of information on topics of interest to the rotary wing community and keeps membership informed of NHA activities. As necessary, the President of NHA will provide guidance to the Rotor Review Editorial Board to ensure the Rotor Review content continues to support this statement of policy as the Naval Helicopter Association adjusts to the expanding and evolving Rotary Wing Community.

ASW, Energized, Focused, and Back in the Forefront; By AWCM David W. Crossan, USN, CHSMWL, N3 ......................................................28 One Ping Only By LT John “Brick” Fritts, USN ...........................................................................................31 ASW, Combined Software Flight Test, and the Path to a Better AMP By LT Bobby Ball, USN and LT Matt Petersen, USN ......................................................32 ASW is a Team Sport By LT Shaun “Cookie” Molina, USN ..................................................................................33 Bridging the Gap between Search and Track: Operator’s View of the Current State of VP/HSM Integration By LT Nicholas Cerny, USN ................................................................................................34 Train Like You Fight: Bolstering ASW Prowess Among FDNF Squadrons By LT Aaron T. Sheldon, USN ..............................................................................................36 Coordinated Anti-Submarine Warfare Training By CDR Dan Murphy, USN, Contributions by LT Michael Hagensick, USN, and LT Paul Ellison, USN ..............................................................................................................38 Pointer Away Now, Now, Now By LCDR Alex “Bender” Haupt, USN.................................................................................41 Why DON’T we do ASW with the P-8s? By LT Kristen McKim, USN, LT Scott Collard, USN and LT Ben Evans, USN............42 The Tyranny of NUMBERS in ASW By LCDR Tom Phillips, USN (Ret.)......................................................................................44

FEATURES

Chris Stefanides’ photo “HSC-6 VERTREP operations during underway replenishment with the USS Theodore Roosevelt”.

TW-5 Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In and NHA Join-Up 2018..................................................20 H-2 Reunion ............................................................................................................................21 Air Boss: Spouses Critical to Aviation Readiness in Era of Dynamic Force Employment By Commander, Naval Air Force, U. S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs...............................22 The Case for Integrating the Tactical Support Unit (TSU) into Fleet Training By LT Eli “Ham” Sinai, USN .................................................................................................23 Land of the Free, Home of the Brave By AWR1 Joshua Davis, USN...............................................................................................26 Realistic Training Opportunities at the FRS By LT Rachel “Wednesday” Winters, USN ......................................................................27

©2017 Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., all rights reserved

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

2

HISTORY Helicopter History ASW Quiz LCDR Tom Phillips, USN (Ret.).....................................................................46 Helicopter Firsts First HIFR By LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.)..........................................................51

Editorial Staff Editor-in-Chief LT Shelby Gillis, USN shelby.gillis@navy.mil Managing Editor Allyson Darroch loged@navalhelicopterassn.org

DEPARTMENTS Chairman’s Brief....................................................................................................................5 In Review ...............................................................................................................................6 Letters to the Editors .........................................................................................................7 From the Organization .......................................................................................................8 In the Community .............................................................................................................10 Industry and Technology SB>1 Defiant Flight Delayed until Early 2019 Sydney J. Freedberg Jr......................................................................................16 Useful Information My PCS Checklist - Taking Stress Out of PCS CDR Erik Wells, USN, Sea Warrior Program Public Affairs ...................17 What About Fido? PCS and Your Pet www.militaryonesource.mil...........................................................................18 Combat SAR Coast Guard Helicopter Pilots in Vietnam Part 3 LCDR Tom Phillips, USN (Ret.).....................................................................48 Radio Check.........................................................................................................................52 Change of Command.........................................................................................................54 There I Was The Coldest War: Modern ASW Operations in the North Atlantic By LTJG Patrick Swain, USN..........................................................................56 Another Routine Night DLQs to USNS Carl Brashear By LT Conor “Dom” Jones, USN..................................................................59 MEDEVAC in the Gulf By LT Amanda “Peeper” Zablocky, USN.....................................................60 MEDEVAC Supporting OIR By LTJG Angela “Tigger” Stearn, USN ........................................................61 Movie Night ......................................................................................................................64 The Great Santini Book Review.......................................................................................................................65 Moscow Airlift by CAPT Mark Liebman, USN (Ret.) The Adventures of a Helicopter Pilot, Flying the H-34 in Vietnam by Bill Collier True Story ...........................................................................................................................66 Maudlin Mission By LCDR Tom Phillips, USN (Ret.) Around the Regions .........................................................................................................70 Pulling Chocks ...................................................................................................................72 Command Updates ..........................................................................................................74 Engaging Rotors ................................................................................................................82 Signal Charlie .....................................................................................................................84

Navy Helicopter Association (NHA) Founders

NHA Photographer Raymond Rivard Copy Editors CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.) helopapa71@gmail.com LT Adam Schmidt, USN adam.c.schmidt@navy.mil CAPT Jill Votaw, USNR (Ret.) jvotaw@san.rr.com Aircrew Editor AWS1 Adrian Jarrin, USN mrjarrin.a@gmail.com HSC Editors LT Christa Batchelder, USN (HSC West) christa.batchelder@navy.mil LT Greg Westin, USN (HSC East) gregory.westin@navy.mil HSM Editors LT Chris Campbell, USN christopher.m.campbe@navy.mil LT Nick Oberkrom, USN nicholas.r.oberkrom@navy.mil USMC Editor Capt Jeff Snell, USMC jeffrey.p.snell@usmc.mil USCG Editors LT Marco Tinari, USCG Marco.M.Tinari@uscg.mil LT Doug Eberly, USCG douglas.a.eberly@uscg.mil Technical Advisor LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) chipplug@hotmail.com Historian CDR Joe Skrzypek, USN (Ret.) 1joeskrzypek1@gmail.com Editors Emeriti Wayne Jensen - John Ball - John Driver Sean Laughlin - Andy Quiett - Mike Curtis Susan Fink - Bill Chase - Tracey Keefe Maureen Palmerino - Bryan Buljat - Gabe Soltero Todd Vorenkamp - Steve Bury - Clay Shane Kristin Ohleger - Scott Lippincott - Allison Fletcher Ash Preston - Emily Lapp - Mallory Decker Caleb Levee - Shane Brenner

CAPT A.E. Monahan, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mark R. Starr, USN (Ret.) CAPT A.F. Emig, USN (Ret.) Mr. H. Nachlin CDR H.F. McLinden, USN (Ret.) CDR W. Straight, USN (Ret.) CDR P.W. Nicholas, USN (Ret.) CDR D.J. Hayes, USN (Ret.) CAPT C.B. Smiley, USN (Ret.) CAPT J.M. Purtell, USN (Ret.) CDR H.V. Pepper, USN (Ret.)

Historians Emeriti CAPT Vincent Secades,USN (Ret.) CDR Lloyd Parthemer,USN (Ret.)

3

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Naval Helicopter Association, Inc.

Corporate Members Our thanks to our corporate members for their strong support of Rotary Wing Aviation through their membership.

Correspondence and Membership P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578 (619) 435-7139

Airbus Avian, LLC Bell Boeing Breeze Eastern CAE Elbit Systems of America Erickson, Inc. Fatigue Technology FLIR GE Aviation Innova Systems Int’l. LLC Kongsberg Vertex Aerospace Lockheed Martin Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems Robertson Fuel Systems, LLC Rockwell Collins Corporation Rolls Royce Science Engineering Services Sikorsky, a Lockheed Martin Company SkyWest Airlines US Aviation Training Solution USAA

National Officers President.......................................CAPT(Sel)Brannon Bickel, USN Vice President…...…………................CDR Dewon Chaney, USN Executive Director........................CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.) Member Services.......................................................Ms. Leia Brune Business Development...........................................Mrs. Linda Vydra Managing Editor...............................................Ms. Allyson Darroch Retired and Reunion Manager ....CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) Legal Advisor ..........................CDR George Hurley, Jr., USN (Ret.) VP Corporate Membership..........CAPT Joe Bauknecht, USN (Ret.) VP Awards ..........................................CDR Justin McCaffree, USN VP Membership ......................................LCDR Jared Powell, USN VP Symposium 2019....................CAPT(Sel) Brannon Bickel, USN Secretary........................................................LT Ryan Stewart, USN Treasurer ................................................LT Chris Hoffmann, USN NHA Stuff.................................................LT Ben Von Forell, USN Senior NAC Advisor..................................AWCM Justin Tate, USN Directors at Large Chairman........................RADM William E. Shannon III, USN (Ret.) CAPT Gene Ager, USN (Ret.) CAPT Chuck Deitchman, USN (Ret.) CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.) CAPT Tony Dzielski, USN (Ret.) CAPT Greg Hoffman, USN (Ret.) CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mario Misfud, USN (Ret.) CDR Derek Fry, USN (Ret.) LT Dave Kehoe, USN Regional Officers Region 1 - San Diego Directors...…................................CAPT Matt Schnappauf, USN CAPT Kevin Kennedy, USN CAPT Billy Maske, USN President..….............................................CDR Dave Ayotte, USN Region 2 - Washington D.C. Directors ....……...…….................................CAPT Kevin Kropp, USN Col. Paul Croisetiere, USMC (Ret.) Presidents .....................................................CDR Ted Johnson, USN CDR Pat Jeck, USN (Ret.)

NHA Scholarship Fund

President............................................CDR Derek Fry, USN (Ret.) Executive Vice President............CAPT Kevin “Bud” Couch, USN (Ret.) VP Operations...............................................................Kelly Dalton VP Fundraising ................................CDR Juan Mullin, USN (Ret.) VP Scholarships.................................................................VACANT VP CFC Merit Scholarship............LT Caleb Derrington, USN Treasurer............................................................Jim Rosenberg Corresponding Secretary..................................LT Kory Perez, USN Finance/Investment..........................CDR Kron Littleton, USN (Ret.)

NHA Historical Society

President............................................CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.) Secretary .......................................CDR Joe Skrzypek, USN (Ret.) Treasurer.........................................................Mr. Joe Peluso San Diego Air & Space Museum............CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.) USS Midway Museum........................CWO4 Mike Manley, USN (Ret.) Webmaster.......................................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) NHAHS Board of Directors..........CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mike Reber, USN (Ret.) CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.)

Region 3 - Jacksonville Director ..................................................CAPT Michael Weaver, USN President..................................................CDR Teague Laguens, USN Region 4 - Norfolk Director ..........................................................CAPT Al Worthy, USN President .........................................................CAPT Joe Torian, USN Region 5 - Pensacola Directors......................................................CAPT Doug Rosa, USN President .....................................................CDR Jessica Parker, USN 2019 Fleet Fly-In.........................................LT Christina Carpio, USN

Junior Officers Council

President ........................................................LT Dave Kehoe, USN Vice President ...........................................LT Arlen Connolly, USN Region 1 ..................................................LT Morgan Quarles, USN Region 2 ......................................................LT Ryan Wielgus, USN Region 6 - Far East Region 3 ....................................................LT Michelle Sousa, USN Director...................................................CDR Dennis Malzacher, USN Region 4 ...................................................LT Tony Chitwood, USN President........................................................CDR Chris Morgan, USN Region 5 .................................................LT Christina Carpio, USN Region 6 ........................................................................... VACANT

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

4

Chairman’s Brief NHA End of the Year Wrap-up

I

t was another great TW-5 Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In and NHA Join-Up this year. I certainly enjoyed myself and hope that those of you that attended did as well. The National Naval Aviation Museum venue was a hit again this year and the addition of the H-2 Seasprite Reunion was a huge success. This was the largest reunion NHA has hosted to date with over 450 people in attendance. For other groups that might be interested in having a reunion event in conjunction with the 2019 Fly-In or upcoming Symposium please contact the NHA Office Retired Reunion Manager, CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) at 619-435-7139 and he will assist you with the planning and execution of whatever might interest your group. I would like to thank everyone that attended this year’s Fly-In events to include the following flag officers: VADM Bill Lescher, USN; RADM Gary Hall, USN (Ret.); RADM Noel Preston, USN (Ret.) and RDML Jay Bowling, USN (Ret.). It was great to see everyone and have the venerable H-2 Seasprite aircraft inducted into the museum along with the program that included viewing Clyde Lassen’s Medal of Honor and having three of the crewmembers involved in the rescue in attendance: CDR Leroy Cook, USN (Ret.), Lassen’s copilot and winner of the Navy Cross, Mr. Bruce Dallas, former AE2 1st crewman/gunner and winner of the Silver Star, and CAPT John “Claw” Holzclaw, USN (Ret.), the rescued F-4 Pilot. The receptions that followed at the museum and evening social at the Fish House were also great events. I’d like to thank everyone at the museum and the Kaman Corporation for doing the restoration. The aircraft looks outstanding. The rest of the week’s activities went great as well. We dodged a little rain throughout the week, all the time being thankful that PCola and Whiting Field were spared from the devastation of Hurricane Michael. The NHA Staff is gearing-up for the upcoming Symposium 15-18 May which is shaping-up to be another good time in San Diego. The Symposium will be held at the Viejas Casino and Resort just of east San Diego in the town of Alpine, CA. We are trying a new schedule format this year with a 2.5 day timeline that should allow more local personnel to attend all the events. Wednesday is the Welcome Social/Members Reunion and Thursday morning will be the opening ceremonies with the Honorable Thomas Modly, the Under Secretary of the Navy has indicated he will be our Key Note Speaker. Thursday evening will be the Flight Suit/Industry Social. Friday will be our signature day with the Captains of Industry and Flag Panels and the hotel is working on some form of entertainment in the form of a concert on Friday evening (entertainment TBD). The Symposium wraps-up with some tours and golf on Saturday morning. Those are just some of the highlights of the events that are planned…please see the NHA website for a DRAFT copy of entire SOE as events are still being finalized. We hope that you will enjoy the new schedule and consider joining us for what promises to be another exciting and professional Symposium in San Diego. Hotel reservations can be made now on the NHA website or by calling the hotel directly. Be sure to mention that you are with NHA for the discounted rate. I will see you there. The holidays are here and I’d like to extend my best wishes to you and your families for some quality down time and a Happy New Year. Looking forward to seeing you in the Spring at the Symposium. Happy Holidays.

RADM Bill Shannon, USN (Ret.) NHA Chairman

NHA Photo Contest 4th Place Winner in the History Category was Chris Napierowski’ s photo; “HM-14 returning to the USS Wasp after departing Copenhagen in 2006. Kronborg Castle sits in the background, which was the inspiration for Shakespearee’s Hamlet”.

5

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

In Review Hello Rotor Review Readers!! By LT Shelby “Conch” Gillis, USN

I

am honored to take the reins as Editor-In-Chief and I hope to keep you all glued to the edge of your seats with the Rotor Review knowledge that is bound within the pages of this magazine. The future is bright for Rotary Aviation and I can not wait to see what it has in store! This editions topic is near and dear to my heart in regards to ASW, but fear not non-Romeo platforms, you have contributed illuminating articles that are just as important and relevant to our current operations. I hope that everyone learns something from this edition, that your love for helicopters is invigorated, and you find yourselves relishing in the fact that we have the best jobs on the planet. Your knowledge of our Rotary Wing community continually impresses me, and I am beyond excited to hear your stories and learn from your experiences in the editions to come. For now, pull up a chair, open your mind, and welcome to this years Winter Topic: Anti- Submarine Warfare. Steady Hover, Down Dome!

NEXT RADIO CHECK QUESTION “What is the one item you wish you had been told to pack for deployment that no one told you to pack?” Send your answer to shelby.gillis@navy.mil or loged@navalhelciopterassn.org. If requested, your replies can be anonymous.

NHA Photo Contest Winners for 2018 The NHA Photo Contest results are in and our members have decided. So many great shots and so hard to choose, but choose you did and here are the top five by popular vote. There were two categories this year; Current and Historical. Gracing our cover the 1st Place in the Current Category is LT Conrad Schmidt, USN’s photo “HSM-51’s Warlord 11 comes in to land on USS Mustin (DDG-89) while on routine patrol in the South China Sea in the 7th Fleet area of responsibility.” • Second Place in the Current Category is LT Ben Taylor, USN’s submission “An MH-60R from HSM-51 sits on the flight deck during a spectacular sunset while on patrol in the Philippine Sea”. • Third Place is Garret Lukasek’s entry “Reaching the Pinnacle”. • Fourth Place is LT Erika Pedersen, USN’s photo “ HSM-73 Battlecats performing hoist exercise with a foreign nation submarine. This is an overhead shot when the aircraft was establishing a hover above the sub.” • Fifth Place winner in the Current Category is CDR Scott Moak, USN’s entry “Sunset DLQ’s with the Fleet Angels”. The Historical First Place, out of many contenders, was Mr. Mario Marini’s photo, “USCG HH-3F Pelican helicopter rescue swimmer training, Old Woman Bay, Kodiak AK 1989.” The photo was taken just prior to Kodiak air station becoming an operational helicopter rescue swimmer unit in November 1989. • Second place is LCDR John Triplett, USN (Ret.)’s “Buno 127785 HU-1 Unit 24 LTJG Bill Stuyvesant Korea 1953”. • Mr. William Bush won Third Place with “Aircrew” He says about this photo “This is the enlisted flight crew that flew the first 5 SH-3 aircraft from Key West to San Diego (Ream Field) upon completion of the factory school. The aircraft were 5 of the first 10 delivered to the Navy and went to HS-10.” • Chris Napierkowski’s submission “ HM-14 returning to the USS Wasp after departing Copenhagen in 2006. Kronborg Castle sits in the background, which was the inspiration for Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet” is our 4th place winner. • There was a three-way tie for Fifth Place, Two were submitted by LCDR Triplett, “BB-62 HO3S-1, 106 3 VADM JJ Clark Korea 1953” and “HU-1 Unit 24 LTJG Bill Stuyvesant in Korea 1953”. The third in the tie for 5th Place was the photo sent by Ms. Anne Alfonso entitled “Welcome Home”. In a break with tradition we have showcased our winners throughout the magazine. Watch the website for the other submissions.. all great shots! NHA congratulates the winners and thanks everyone who submitted photos and our members who voted for their favorites. Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

6

Letters to the Editors It is always great to hear from the members of NHA. We need your input to ensure that Rotor Review keeps you informed, connected and entertained. We strive to provide a product that meets demand. We maintain many open channels to contact the magazine staff for feedback, suggestions, praise, complaints or publishing corrections. Your anonymity is respected and please advise us if you do not wish to have your input published in the magazine. Post comments on the NHA Facebook page or send an email to the Editor in Chief; shelby.gillis@navy.mil or the Managing Editor; loged@navalhelicopterassn.org. You can use snail mail too. Rotor Review’s mailing address is: Letters to the Editor c/o Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578. Subject: Coastie article Date: December 11, 2018 at 5:17:20 AM PST To: Thomas Phillips tom.phillips.seawolf@gmail.com Hi Tom, Wanted to compliment you on your article “Coast Guard Helicopters in Vietnam.” As a postwar rotary guy, I was not aware of the Coastie’s exploits and heroism during the war. Especially enjoyed the way you described the crew’s emergency landing at Phu Bai AB after a tail rotor problem- something I never had to worry about while flying the H-46! Hope all is well. Have a nice holiday. Best regards, Larry -Larry Carello www.larrycarello.com

Naval Helicopter Association

Rotor Review Submission Guidelines

2018-2019 Submission Deadlines and Publishing Dates Winter 2019 (Issue 143) .............November 18 / January 10, 2019 Spring 2019 (Issue 144) ....................... March 19 / April 30, 2019 Summer 2019 (Issue 145)........................July14 / August 10, 2019 Fall 2019 (Issue 146) .................September 18 / October 10, 2019 Articles and news items are welcomed from NHA’s general membership and corporate associates. Articles should be of general interest to the readership and geared toward current Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard affairs, technical advances in the helicopter industry or of historical interest.

All submissions can be sent to your community editor via email or to Rotor Review by mail or email at loged@navalhelicopterassn.org or Naval Helicopter Association, Attn: Rotor Review P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578

7

1. Articles: MS Word documents for text. Do not embed your images;within the document. Send as a separate attachment. 2. Photos and Vector Images: Should be as high a resolution as possible and sent as a separate file from the article. Please include a suggested caption that has the following information: date, names, ranks or titles, location and credit the photographer or source of your image. 3. Videos: Must be in a mp4, mov, or avi format. • With your submission, please include the title and caption of all media, photographer’s name, command and the length of the video. • Verify the media does not display any classified information. • Ensure all maneuvers comply with NATOPS procedures. • All submissions shall be tasteful and in keeping with good order and discipline. • All submissions should portray the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard and individual units in a positive light.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

From the Organization President’s Message

By CAPT (Sel) Brannon “Bick” Bickel, USN

A Strategic Level Challenge

G

reetings from San Diego and happy holidays. This edition of Rotor Review is focused on all things Anti-Submarine Warfare. Knowing that submarines represent a strategic level challenge to our national defense, we should be proud to represent the only organic ASW capability within the Carrier Air Wing. Additionally, our ASW prowess combined with the surface combatants, Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Force assets forward, and submarines within the Carrier Strike Group is essential for the protection and defense of our afloat military forces against submarine threats. Based upon the great power competition in the world today, Combatant Commanders and Fleet Commanders are demanding more and more ASW capability. One of the most exciting times during my last tour in the fleet with HSM-37 Easyriders was during a Submarine Commanders Course in Hawaii. My squadron embarked helicopter detachments on three of the combatants stationed at Pearl Harbor. The P-3’s from CPRW-2 in Kaneohe were flying around the clock, and there was tremendous synergy between the surface and airborne assets fighting the submarine threats against our Surface Action Group. The P-3’s were conducting open ocean searches and ships and helicopters were refining any acoustic contact. Sonobuoys and torpedoes were raining from above. The team was holding down submarines with expert application of tactics, techniques, and procedures. The preparation, execution, and lessons learned from that exercise was the best and most practical application of ASW training that I’ve seen in my career. It was on par with the Theater ASW Exercises that our Carrier Strike Groups conduct after deploying as a fully certified team. Having actual contact time provided my crews with tremendous lessons that better prepared them for future deployments. There are many more examples of similar ASW experiences throughout this edition. It’s my assertion that we need to find more ways to prepare crews in similar fashion outside of HARP, C2X, and ACTC level advancements. Lastly, in preparation for next year’s NHA Symposium, please spend some time thinking about the innovations that we need in the Rotary Force. What do we have, and what do we need to be more agile and lethal in future combat operations. I hope that we can discuss how we train, the tools that we use today, the things that we need in the future. Weapons, sensors, increased on-station time, long range ASW assets in the CVW… there are so many topics to discuss. In the meantime, enjoy this edition of Rotor Review, and I’ll see you on glideslope. Bick

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

8

Executive Director’s Notes By CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)

A

nother successful Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In and NHA Join-Up is in the books. We enjoyed a great week of activities and also had a very successful H-2 Seasprite Reunion and Aircraft Dedication at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola. Hurricane Michael luckily spared Pensacola and while we had a couple days of rain we were able to execute all the events. Thank you to the hospitality of Commodore Dave Morris, USMC and CAPT Doug Rosa, USN from TW-5 and CDR Jessica Parker, USN CO of HT-8 and her team of LT Christina Mullins and LT Kristina Carpio that made the Fly-In a hit. Thank you also to the countless others that arranged the events and to our Corporate Members who sponsored the socials and provided the necessary support for everyone to have a good time. We have had a pretty significant turnover on the NHA National Staff and I would like to take this opportunity to welcome our new officers and say thank you to our outgoing members for their service. Farewell to: CDR Aric “Bull” Edmonson, USN – NHA Region One President and Hawk Ball Coordinator Welcome aboard to: CDR Dave “3D” Ayotte, USN, CO HSC-21 Farewell to: CDR Justin “Juice” McCaffree, USN, CO HSC-23 - Vice President/Awards Welcome aboard to: CDR Rick “Shooter” Haley, USN, CO HSC-21 Farewell to: LT Andy Hoffman, USN, HSM-41 - JO President Welcome aboard to: LT Dave “FIGJAM” Kehoe, USN, HSM-41 Farewell to: LT Shane Brenner, USN, HSM-41 - Rotor Review Editor Welcome to: LT Shelby ”Conch” Gillis, USN, HSM-41 Farewell to: LT John Kipper, USN, HSC-3 - Stuff/Projects Officer Welcome aboard to: LT Ben Von Forell, USN, HSC-3 Farewell to: LT Rick Jobski, USN, HSC-3 - Secretary Welcome aboard to: LT Ryan “Hot Rod” Stewart, USN, HSC-3 Farewell to: LT Diane Sebastiano, USN, HSC-3 - Treasurer Welcome aboard to: LT Chris Hoffmann, USN, HSC-3 Congratulations go out to Master Chief Justin Tate, USN our NHA Senior Enlisted Advisor as he was just nominated and elected to the NHA Board of Directors! RADM Pat McGrath, USN (Ret.) is in the process of turning over with RADM Bill Shannon, USN (Ret) our current NHA Chairman. Admiral McGrath lives and works here locally in San Diego so you may see him periodically in and around the NHA office spaces as he plans to attend our monthly meetings when he can. Please welcome him if you see him and he will officially take over the job in the spring at the 2019 at the Symposium. I want to publicly thank the H-2 Reunion Group under the leadership of RADM Gary Jones, USN (Ret.), CAPT Ernie Rogers, USN (Ret.) and CAPT Earl Rogers, USN (Ret.) for their generous donation to NHA after what was a very successful reunion in PCola. We hope that everyone has had the opportunity to spend some quality time with friends and family over the holidays as we continue to work the details of the upcoming 2019 Symposium. The theme for 2019 is “Rotary Force Innovation and Integration” and we will be at the Viejas Casino & Resort in Alpine, CA just east of San Diego. We hope that you will consider joining us for what is shaping up to be an outstanding event. This year we are trying a compressed schedule that should allow more local personnel to attend all or most all of the events. You also might consider staying overnight at the resort as we have per diem pricing for all the rooms and the hotel has just opened a new wing with all new rooms. Download the NHA phone app or check the website for more details. You can register for your rooms online now. Have a great holiday season and we’ll hope to see you in the new year. Keep your turns up. Regards, CAPT P., USN (Ret.) 9

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

In the Community Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society By CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)

We just completed the registration for the NHA Historical Society (NHAHS) to become a recipient of donations from the Amazon Smile Program. NHAHS is a 501 c 3 non-profit and is eligible for this program so .5% of your purchases on Amazon will be donated to NHAHS when you shop using the Amazon Smile Program. You can register online and select the Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society as your charity of choice and then make your future purchases through the Amazon Smile Program and your donations will start flowing to the Historical Society. It costs you nothing and it is easy to do. So….sign-up today at http://smile.amazon. com/about. Hope you and your families have a safe and happy holiday season. Keep your turns up. Regards, CAPT P (Ret.)

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

10

Naval Helicopter Association Scholarship Fund Update By Kelly Dalton, Vice President of Operations NHASF

I

t’s that time of the year again—the time when we reflect thoughtfully on all the recent opportunities that have helped us grow, when we send written missives chronicling our (or our children’s, or grandchildren’s) many accomplishments, and when we look ahead purposefully to what next year has in store. I’m referring, of course, to the NHA Scholarship Application season! The NHA Scholarship Fund will be accepting applications for our many undergraduate and graduate scholarships until January 31st, 2019. Eligible applicants must be a current NHA member—or the spouse, child, or grandchild of a current NHA member—planning to pursue an undergraduate or graduate degree during the 2019-2020 school year. We award scholarships worth up to $5000 annually based on an applicant’s record of academic excellence; individual drive; service to family, community, and nation; and potential for professional and personal success. For more information and the online application, please visit our website at http://www.nhascholarshipfund.org. It’s also, of course, a time of the year when we may feel particularly inspired to give back to our communities, and donating to the NHA Scholarship Fund is a worthwhile way to do exactly that! Contributions to the fund can be made either through our website, or through the CFC, using code 10800. We welcome interested corporate sponsors, as well; our sponsors have included CAE Systems, FLIR, Lockheed Martin/ Sikorsky, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon. Additionally, we are proud, and extremely grateful, to announce that in early November the USS Midway Foundation awarded the NHA Scholarship Fund a $10,000 “Pillars of Freedom” grant, given to non-profit organizations that serve active duty service members, veterans, and their families. As the holidays come to a close and you look ahead to all that 2019 will have in store, please keep in mind that supporting the active duty and veteran members of NHA—and their families—in the pursuit of their goals of higher education is probably the easiest New Year’s resolution you’ll ever keep!

11

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

In the Community A View from the Labs: Supporting the Fleet by CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

What’s Old is New

C

an anyone remember when ASW wasn’t a wicked hard problem for the Navy and for naval rotary wing aviation? I sure can’t, and I flew my first flight as a naval aviator in 1970. As my friends in the submarine community like to say, “There are only two types of ships – submarines and targets.” The question is: How do we make adversary subs sunken targets? While there are many things we have done – and continue to do – to give our Navy the edge over enemy submarines: Training, tactics, wargaming, new CONOPS and the like. But at the end of the day, breakthroughs in ASW have always been paced by technology and by pushing the edge of the envelope in what technology might bring to the game. What’s important, I believe, is trying new technologies and not being afraid of failure – because failure can ultimately lead to success – just not the way we think. Here’s an example. Who remembers DASH? As the United States became involved in the Vietnam War during the early 1960s, the Navy renewed its efforts to find a way to field unmanned systems to meet urgent operational needs. At that time, all sea-based aviation was concentrated on the decks of Navy aircraft carriers and large-deck amphibious assault ships. Surface combatants—cruisers, destroyers and frigates—had no air assets at their disposal. The solution was to adapt a technology that had been in development since the late 1950s to field the QH-50 DASH (Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter). In April 1958 the Navy awarded Gyrodyne Company a contract to modify its RON-1 Rotorcycle, a small two coaxial rotors helicopter, to explore its use as a remote-controlled drone capable of operating from the decks of small ships. The Navy initially bought nine QH-50A and three QH-50B drone helicopters. By 1963 the Navy approved large-scale production of the QH-60C, with the ultimate goal of putting these DASH units on all its 240 FRAM-I and FRAM-II destroyers. In January 1965 the Navy began to use the QH-50D as a reconnaissance and surveillance vehicle in Vietnam. DASH was also outfitted with ASW torpedoes to deal with the rapidly growing Soviet submarine menace, the idea being that DASH would attack the submarine with Mk-44 homing torpedoes or Mk-57 nuclear depth charges at a distance that exceeded the range of submarine’s torpedoes. But by 1970, DASH operations ceased fleet-wide. Although DASH was a sound concept, the Achilles heel of the system was the electronic remote control system. The lack of feedback loop from the drone to the controller, as well as its low radar signature, accounted for 80% of all drone losses. While apocryphal to the point to being a bit of an urban legend, it was often said the most common call on the Navy Fleet’s 1MC general announcing systems during the DASH-era was, “DASH Officer, Bridge,” when the unfortunate officer controlling the DASH was called to account for why “his” system had failed to return to the ship and crashed into the water. But the concept of delivering a torpedo against an enemy submarine took hold, and the Navy pursued a program it called “LAMPS Mk1” where it took an off-the-shelf helicopter, the H-2 and put it on current frigates like the Knox-class to provide a capability that – while not state-of-the-art and far from perfect, ultimately led to LAMPS Mk III and now the MH-60 community. The point is this: Not every new technology succeeds, but to fail to try ensures failure. Those of you in flight suits owe it to yourselves to pulse the technical community to come up with ideas that just might work and turn the ASW game in our favor. There are plenty of inviting targets out there – and they’re called Chinese and Russian submarines. Who will find the next breakthrough technology that just might be sitting on the shelf waiting to be discovered?

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

12

Aircrewman’s Corner By AWCM Justin Tate, USN

Fellow Aircrewmen

G

ood day to all of you! Another great Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-in/NHA Join Up has come and gone. It is always a great time to meet the Pilots and Aircrewmen that are in their initial training. This was amazing to answer all the questions that the students have to make sure they have full visibility on what their future holds. A big “THANK YOU” to AWRC Stephen Griffin and his cadre of volunteers that made the events even more spectacular than last year. Thank you again and a job well done. This issue of Rotor Review is “ASW.” When I joined the Navy and went through all the initial training to be an Aircrewman, the ASW training for the threats at that time was of the highest priority. As time went on and warfighting focuses changed, ASW fell lower on the priority list. We are now back to a dire focus on ASW. This is where we will have to remember how we trained years ago, modernize it and train all of our shops to know what they are looking for and how to exploit the aircraft systems to deter whatever the adversary. Getting in the books, paying attention during intel briefings and understanding the aircraft is a start in the right direction. We as Aircrewmen have a vital role in ASW and we need to do all we can to make sure we are ready when called upon. On another note, I am transferring and this is my last article and month as the Senior Enlisted Advisor to the NHA National Staff. AWRCM Nate Hickey will be my replacement and be an amazing fit with the staff and each and every one of you. It has been an amazing venture being part of the NHA National Staff. The staff and partners of industry have been amazing and really made these couple of years a great and memorable time. I want to personally thank CAPT Personius,USN (Ret.) CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret) Leia, Linda and Allyson for a memorable tour and always continuing to make Aircrewmen a part of all you do. I will not forget all that we have worked through. “Thank you very much!” You guys rock! I appreciate everything that all of you do. Keep up the great work and continue to challenge yourselves to be the best Aircrewman. Learn all you can to be able to fight the aircraft to its fullest ability. Thank you for all you do and I look forward to seeing you around the Fleet.

Fly Safe!

A View from the JO Council

By LT Andrew “Hassle” Hoffman, USN

Parting Words

F

leet Fly-in this past October was an absolutely awesome time! Going back to Pensacola and engaging with the students who are just starting their journey is always a blast. The various panels were informative, with many good questions asked by students, pilots, aircrew, and industry alike. Pensacola provided us with a couple good weather days for flying which helped get the students pumped up. Big thanks to all those who helped organize the events. To all the students I spoke with: I hope I was able to help in some way when answering your questions! The most important thing to remember is that you are going to have a great and rewarding experience no matter which community you end up becoming a part of. Each platform brings a unique skillset and value to the mission. Each platform has a community filled with amazing maintainers, pilots, aircrew, and leaders. You can’t go wrong! On a personal note, this past Fleet Fly-in was my last as an active duty Naval Aviator, as I’ll be separating early next year. I’ve turned over the JO President position to LT Dave “FIGJAM” Kehoe, but will remain active within NHA. Looking back, I truly can’t think of anything better I could’ve done with the past 10 years of my life. I had the privilege of being a member of the greatest organization and team I’ll ever be a part of. Thanks to all the amazing Skippers, XOs, DHs, ridiculous JOPA, and crazy aircrew who made it all that it was. I look forward to staying in touch with all of you and will be waiting to help each of you in any way I can when your time comes to start the next chapter. Until then, keep being the best at what you do and fly safe. Cheers, Hoff 13

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

In the Community Door Gunner Diaries By AWS1 Adrian Jarrin, USN

There’s No Requirement for That

W

elcome back flyers to another edition of Door Gunner Diaries. Last issue we focused on human systems technology or lack thereof with the two most commonly used helicopter flight helmets throughout the Department of Defense (DoD) HUG-56/P and HUG-84, both of which have technology that are nearly 30 years old. We also highlighted the fact that it’s been over 20 years since these helmets have undergone any performance review, according to a performance assessment report by U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory. (USAARL,1996)

the system under development to a level that can be built. In other words, does the system do what it is supposed to do? How well does the system do its function? These are examples of functional and performance requirements. In the DoD the requirement process is governed by the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS). The JCIDS process ensures the capabilities required by the DoD are identified and their functional and performance requirements are developed. What is the requirements development process in the DoD? The DoD requirements development process is long and complicated which is an understatement to say the least. The simplest way to describe the requirements development process in the DoD, that it is a set of processes that produces requirements for a product. The first phase in requirements development is the requirement analysis of the system engineering process. In other words, it’s an interface between internal activities and external sources providing inputs to the process. For a classic DoD program, the DoD must first provide four mandatory documents to even start the requirement development process. Those documents are: Initial Capabilities Documents (ICD), Capability Development Documents (CDD), System Requirements Documents (SRD), Weapon System Specification (WSS), and Capability Production Document (CPD). At this point, no actual requirement is developed yet. Who is still with me?

In this issue, I want to discuss the requirements development process in the DoD and why its’s so imperative for helicopter end users to be more engaged and familiar in this process. Why requirements and why couldn’t I have chosen a more exciting topic to talk about? Well I apologize in advance to those people who have preconceived notions of the requirements process. I would encourage everyone out there in the rotary wing community who is sick and tired of waiting for technology to catch up and learn how they can play a role in speeding up the innovation process. This issue is specifically centered around helicopter human system technology, i.e. flight gear, so let’s get started.

The next phase is broken into six steps: 1. Gather and Develop Requirements. 2. Write and Document Requirements. 3. Check Completeness. 4. Analyze, Refine, Decompose Requirements. 5. Verify & Validate Requirements. 6. Manage Requirements.

“THERE’S NO REQUIREMENT FOR THAT.” Does this phrase sound familiar? Have you ever had an idea you knew would improve your job or even your community? But when you finally decided it was time to bring it up to the chain of command you were told, “there’s no requirement”. To the warfighter, those words are extremely discouraging and could have devastating consequences to future innovators who want to just improve the welfare of end users on the battlefield. Think about how many great ideas have been turned down over the years throughout military history. Ideas that could’ve brought innovation to our workspaces and our communities, but were turned down because there “wasn’t a requirement for it”.

That’s just the DoD’s bare minimum to develop a requirement. Other areas that DoD program managers, and system engineers need to know are: requirements tracing, capability development tracking and management tool, feasibility assessment, requirement checklist, joint capability area attributes, joint service specification guides, standardization, requirement types, requirements allocation, requirement development sequence, and requirement evaluation. That’s it. That’s the DoD requirements process in a nutshell. Unfortunately, the DoD requirements process will most likely never change. But what if instead of trying to reinvent the process we created a more VFR direct conduit so requirements can be revisited with more regularity and that those requirements take into account current end user’s

How are requirements actually defined in the DoD? The systems engineering standard defines requirements as “something that governs what, how well, and under what conditions a product will achieve a given purpose.” Requirements outline functions, performance, and environment of Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

14

experiences. For example, one question I get frequently asked about helicopter human system requirements throughout the community is; how often do requirement offices review helicopter human system requirements and engage with end users on the flight gear they use every day. From an end user’s perspective, I can say the flight gear we use every day is outdated and is in desperate need of modernization.

I believe one way to address this human systems technology problem is by introducing a fresh new approach to gathering the end users experience and knowledge. Requirements must reflect accurately the needs and wants of our rotary community and address current capability gaps so we’re not using the same logic and reasoning that went into designing these helmets almost half a century ago.

Why do I bring this up? What if I told you the main reason we still fly with flight helmets that are nearly 30 years old, is because there’s no requirement to replace them. This is a huge human system problem and because there are only two helmets approved by the DoD, the problem affects rotary communities DoD wide.

Albert Einstein once said “we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when created them.” Until next time. Fly smart.

REQUIREMENT DESIGNED BY THE END USERS.

??? And for your edification ladies and gentlemen, I present -The Problem.

You are here x

An Overview of the Integrated Defense Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Life Cycle Management System

15

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Industry and Technology Future Vertical Lift: SB>1 Defiant Flight Delayed Until Early 2019 By Sydney J. Freedberg Jr.

T

he SB>1 Defiant, a high-speed helicopter aimed at future Army missions in major wars, won’t make its first flight this year after all. Unspecified but “minor” issues discovered in ground tests will push first flight back “two or three weeks,” co-developers Sikorsky and Boeing said this morning. Meanwhile, the other contender for the Future Vertical Lift aircraft, Bell’s V-280 Valor, will celebrate a year of flight tests next Tuesday. That reflects, at least in par, a fundamental difference in approach. While Bell’s V-280 uses tiltrotor technology, proven in widespread service on the V-22 Osprey since 2007, the Defiant uses Sikorsky’s revolutionary compound helicopter technology, which promises superior agility — but which has only actually flown in two experimental aircraft, the X2 and S-97 Raider, both of which are much smaller than Defiant. Defiant and Valor are both candidates for the mid-sized FVL variant, what the Army now calls the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA, pronounced “flora”). The Army wants to start building the new assault aircraft ASAP to replace its UH-60 Black Hawks. The UH-60 is a Cold War design that’s been the workhorse in Afghanistan and Iraq, but it lacks the speed and range that military futurists think will be required to penetrate advanced antiaircraft defenses like Russia’s or China’s. (The Army’s also urgently looking for a new armed scout, the Future Armed Reconnaissance Aircraft, and there the leading contender is Sikorsky’s S-97, which is smaller than Defiant and already in flight testing).

told reporters. The Defiant and Valor are technically only Joint MultiRole demonstrators, not competing Future Vertical Lift prototypes, but the Army wants to start a program of record in 2021 and the demonstration phase is widely viewed as a de facto competition. So when would be too late for first flight? “We haven’t come up with a date that, ‘oh my goodness, if we haven’t flown by this, this time, we’re too late,’” said Randy Rotte, Boeing’s director of cargo aircraft and FVL. “We’ve been really focused on…when we have to have the data to them, which is somewhat fuzzy and open-ended because the Army’s been willing to accept (test data) over a longer period of time.” The crucial data, of course, will come from flight testing: “We’re working with the Army now on how long we’ll be able to do that,” Rotte said. Inevitable Surprises What’s been the issue? It is not previously reported problems with the

After fixing some “minor” issues discovered during ground tests, the SB>1 will still fly early next year, in plenty of time to provide data to the Army for its ongoing Analysis Of Alternatives, the company officials Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

transmission gearbox or rotors, Rotte said. “The good news is, for all intents and purposes, for everything we know, those issues are behind us,” he said. “They were both about manufacturing; they were not about necessarily design.” The gears turned out not to be quite hard enough, so they had to be reground. The unusually long, stiff rotor blades a compound helicopter requires — to achieve high speeds without the crippling vibrations a conventional chopper would encounter — proved “a bigger challenge” than expected to manufacture with the existing tools. The modified transmission has “been through all its testing (and) passed with flying colors,” Rotte said. The blades have been running in ground tests since last month: “We haven’t seen anything yet that would be an issue or a problem. So far so good, I’m knocking on wood when I say this.” Whatever the latest issue was, it only appeared when the companies put all the components together and ran them

The Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 Defiant 16

“We’ve had a couple of runs on the PSTB,” said Rich Koucheravy, FVL director. for Sikorsky (now part of Lockheed Martin). “The initial two, three runs, we did have some minor discovery. I won’t get into the nature of the discovery, (but) it’s a relatively mundane thing that has to be fixed.” “We expect these sorts of things to come up when you run a configuration stand for the first time,” Koucheravy said. “That’s the purpose of building the PSTB.” No amount of

component-by-component testing or computer modeling can predict all the interactions when you put everything together and turn it on, particularly vibration and heating. But traditionally, you don’t discover those issues until you’ve got the first prototype in ground tests. By building the Power System Test Bed and running it even as the actual aircraft was still under construction, Koucheravy argued, you can find and fix the inevitable problems earlier. The changes are being made to both the testbed and the Defiant aircraft itself, Koucheravy and Randy said, which is taking about “two to three

weeks.” Then the testbed will be back in operation and the Defiant will be starting its first-ever ground tests. So first flight will likewise be delayed two or three weeks, into early 2019 — assuming no further surprises. “That would be great,” Rotte said. “I’m not sure if that would happen or not.” The companies could have kludged together something sooner, “a quick fix to get up in the air,” Koucheravy said. “That’s not the type of development work we do.”

Erickson awarded U.S. Pacific Command Aerial Services Contract By Hayden Olson. Erickson Inc.

E

rickson Incorporated, a leading aerospace manufacturer and aerial services company, has been awarded a firmed fixed price, indefinite-delivery/ indefinite-quantity contract for a base year with options for three additional years. The contract will provide dedicated rotary wing and fixed wing aircraft to the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) area of responsibility (AOR). The USPACOM AOR is defined as, but not limited to, continental Asia, Philippine Islands, and countries supporting operations in the Philippines. Erickson will execute the contract utilizing organic rotary and fixed wing Erickson platforms. “Erickson is proud to perform this mission in support of the Department of Defense and the Warfighters. Our combination of experience supporting these operations, and ability to utilize the B214ST Helicopter, a platform where we are Bell’s product support provider, enables us to offer exceptional value and performance to U.S. Government customers.” Kevin Cochie, VP & GM, Erickson Defense and National Security. 17

About Erickson Erickson is a leading global provider of aviation services and operates, maintains and manufactures utility aircraft to safely transport and place people and cargo around the world. The Company is self-reliant, multifaceted and operates in remote locations under challenging conditions specializing in Defense and National Security, Manufacturing and MRO, and Commercial Aviation Services (comprised of firefighting, HVAC, transmission line, construction, timber harvesting, oil and gas and specialty lift). With roots dating back to 1960, Erickson operates a fleet of more than 50 aircraft, is headquartered in Portland, Oregon, USA, and operates in North America, South America, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia Pacific, and Australia. For more information, please visit our website at www.ericksoninc.com.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Industry and TECHNOLOGY

in their Power System Test Bed (PSTB), essentially a copy of the Defiant aircraft that’s bolted to the ground.

Useful Information My PCS Checklist - Taking Stress Out of PCS By CDR Erik Wells,USN, Sea Warrior Program Public Affairs

T

he latest upgrade to MyNavy Portal (MNP) includes a checklist to guide Sailors and their families through their next Permanent Change of Station (PCS) move. My PCS Checklist allows Sailors to easily create their own personalized move checklist, and can be found in the Assignment, Leave, and Travel section of MNP under the Career and Life Events drop down menu. There is no question that PCS moves are challenging, whether it is a single Sailor heading across country or a family moving overseas. The process of relocating can be a source of personal, financial and family stress and it requires a great deal of logistical planning. My PCS Checklist makes the process better. Sailors can now create their own personalized checklist by using an intuitive, web-based program, to guide them through the PCS process and help eliminate unnecessary stress. “Creating the checklist is easy,” said CAPT Chris Harris, director, distribution management division, Navy Personnel Command. “Sailors answer a few questions in the online checklist, starting with their official detachment date, which automatically generates a personalized, step-by-step checklist that calculates the number of days to complete each item until their move from their current command. Sailors can print out their checklist at work or email it to a spouse, parent or anyone with whom they want to share the information.” The checklist is broken down into four categories – Shipping Household Goods, Family Move, Money and Sailor Admin. Based on the detachment date selected, the checklist outlines necessary activities, due dates and includes tips and sources of support for each category. The program includes a taskbar that indicates how far along Sailors are in completing their activities and they will receive alerts to remind them to complete the tasks to stay on their PCS timeline. “MyNavy Portal addresses one of the major issues Sailors face when managing their careers – they have to use too many websites to complete routine tasks for managing their careers,” said Dave Driegert, PMW 240 assistant program manager, Single Point of Entry for MNP. “My PCS Checklist is the newest tool for Sailors and joins other recently-available applications like MyRecord Web 1.0 and electronic Personnel Action Request (ePAR)/1306. MNP is growing all the time. In the months ahead, Sailors will be able to access an increasing number of new features and tools.” Sailors should work with their command pay and personnel administrator if they have any questions concerning PCS policies and procedures. They may also contact MyNavy Career Center 24/7 at askmncc@navy.mil, or toll-free at 833-330-MNCC (6622). In addition to PCS information, MNP provides Sailors links to other webpages and resources – all in one convenient location. Get more information about the Navy from US Navy facebook or twitter. For more news from Chief of Naval Personnel, visit www.navy.mil/local/cnp/.

Do We Have Your Current Address?

Rotor Review is mailed at the periodical rate so the post office will not forward magazines. You can update your information through the“Members Only” portal on the NHA Website,www.navalhelicopterassn.org. If you prefer the digital edition of Rotor Review just let us know. We are happy to change your preferences. Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

18

What About Fido? PCS and Your Pet

I

f you consider your pet a member of the family, your first thought may be to bring your pet along when you receive permanent change of station, or PCS, orders. Many military families do take their pets with them, but it requires some upfront planning and preparation. Here are some things to consider as you prepare your pet for PCS, both in the U.S. and abroad. Moving in the U.S. There may be a limit to the number of pets you can have, or other rules that apply on a military installation. Look up the regulations for your new installation on MilitaryInstallations. Check to see if there are any rules for bringing your pet into the state where you’ve been assigned. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s website can tell you if there are any restrictions. Before your move, make sure you take your pet to the vet. Making sure your pet is healthy and has updated immunizations can make a domestic or overseas move go smoother. Reduce the chances of your pet getting lost in transit by getting her an ID tag, having your vet insert an ID microchip under her skin, or taking her picture for easy identification. If your pet will be coming with you in your car, have him spend some time in the car ahead of your move to get used to it. Have him ride in a pet crate if that is how he will travel. Moving to another country Search for your new installation on Military Installations to find any rules and regulations related to bringing in pets. Contact the consulate or embassy in the country you are assigned to and learn about the rules for bringing in pets. Ask if your pet will need to be quarantined upon entering the country and the cost of quarantine. The Department of Defense may reimburse you up to $550 for that expense. Check airline travel requirements, such as whether your pet will need to travel in a crate or if you will have to reserve space on the flight for your pet. The Department of Defense will not reimburse you for the relocation cost associated with moving your pet from one country to another. Moving can be a challenge for you and your pet, so make it easier by finding out what you need to know before your next PCS.

DID YOU KNOW? When you shop at smile.amazon.com, you’ll find the exact same low prices, vast selection and convenient shopping experience as Amazon. com, with the added bonus that Amazon will donate a portion of the purchase price to the Naval Helicopter Historical Society.

19

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

USEFUL INFORMATION

www.militaryonesource.mil/

Fly-In 2018 2018 Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In

HT-8 and HT-28 Staff with the 2018 Fleet Fly-In Coordinators; LT Kristina Mullins, USN and LT Christina Carpio, USN.

HT-8 Students

Attendees gather at the Massif exhibition table in the National Naval Aviation Museum. Lunch at the Museum

Helicopter Aircrew Candidates, Aviation Rescue Swimmer Students, and AW “A” School Students recite the Aircrewman’s Creed, in a video message for RADM Tomaszeski, USN (Ret.) as motivation for his continued dedication and recovery.

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

20

2018 H-2 Reunion in Pensacola

Navy.

ifty five years ago the Kaman Corporation completed and delivered the first of 240 Seasprites to the United States

In 1973 the SH-2F Seasprite was selected to serve as the LAMPS MK 1 helicopter to deploy on U.S. Navy Destroyers, Frigates and Cruisers. After 20 years of LAMPS service the SH-2F was retired from the Navy inventory and replaced with the LAMPS MK III SH-60B. It was decided that in conjunction with the induction of Seasprite BuNo 151312 into the National Naval Aviation Museum we should have a reunion to celebrate and recognize the many men and women who served as Kaman Tech Reps, administration personnel, aircraft maintainers, aircrew and pilots. The ceremony was held October 24-26, 2018 in Pensacola Florida in conjunction with the 2018 TW5 Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In and NHA Join-Up.

The H-2 Reunion and Ceremony Reception brought squadronmates together again

D

uring October's Fleet Flying this year, HT-8 sponsored a panel discussion at Whiting Field. The panel consisted of members of CDR Clyde Lassen's crew and the rescued pilot from their Vietnam rescue in 1968. Present for the presentation and Q&A discussion were CDR Leroy Cook, USN (Ret.) who was a LTJG and LT Lassen's copilot, former AE2 Bruce Dallas who was the door gunner and rescue aircrewman and CAPT John Holtclaw, USN (Ret.) who was the LT F-4 pilot whom they rescued. They all related their recollections of the rescue which resulted in the Medal of Honor for LT Lassen, the Navy Cross for LTJG Cook and the Silver Star for AE2 Dallas. LT Lassen and his crew were attached to HC-7, flying and SH-2 Seasprite off the USS Preble (DLG-15) at the time. LT Lassen was the first naval aviator and the fifth Navy man to be awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery in Vietnam.

Panelists and HT-8’s commanding officer, (left to right), Former AE 2 Bruce Dallas, USN, CDR Jessica Parker, USN, CAPT John Holzclaw,USN, and CDR Leroy Cook, USN. 21

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In 2018

F

Features Air Boss: Spouses Critical to Aviation Readiness in Era of Dynamic Force Employment By Commander, Naval Air Force, U. S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs

C

ommander, Naval Air Forces (CNAF) Vice Adm. DeWolfe H. Miller III, USN told Naval Aviation’s senior enlisted leadership and their spouses the importance of their role in communicating to Sailors the changes in deployment cycles at the Naval Aviation Enterprise Command Master Chief (CMC)/Senior Enlisted Leader (SEL) Symposium Nov. 5-7.

Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy (MCPON) Russell Smith addresses the audience at the Naval Aviation Enterprise 2018 Command Master Chief/ Senior Enlisted Leadership and Spouse Training Symposium. Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Luke Perry, USN.

“You have a profound impact on our Sailors and their families.” Miller said. “We are in a great power competition. The habit patterns that you teach your Sailors, and the resilience you provide for our families will kick in when we go into a highend fight. And I just want to say, ‘Thank you.’” The annual aviation CMC/SEL symposium hosted 130 Command Master Chiefs and Senior Enlisted Leaders from aviation commands around the globe, and for the first time included their spouses. Fifty-five spouses attended the symposium, receiving briefings on everything from aviation readiness to family support programs.

“I jumped out of my seat when my husband sent me the email, because I was so excited that they thought enough of us as spouses to come and take part in this symposium,” said Karla Reeder, wife of the VAQ-140 CMC. “As experienced military spouses we need to be able to educate the junior sailor spouses and junior officer spouses on topics they need to know about.” Warfighting and readiness were central topics of the symposium, with Dynamic Force Employment (DFE) and changing deployment paradigms being a central theme. “As we continue with DFE and unpredictability, we’re going to leave and spouses and families aren’t going to really understand why that unpredictability is there,” said FORCM (AW/SW/NAC/IW) James Tocorzic, the CNAF Force Master Chief. “We need all members of our triad spouse team to understand that, and be able to communicate that all the way to the spouses of our deckplate sailors.” Tocorzic added that Sailors who have only served in recent decades may not understand the reasons for unpredictable schedules and restricted communications, making education a key role for leadership. “We have demonstrated Naval Aviation’s airpower over the last two decades over land in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. A maritime fight with peer competitors, though, will absolutely will be different for our families. We will not have the ability to communicate via email and social media like we do today.”

Retired Chief Photomate David Harper leads a tour of command master chief spouses aboard the USS Midway Museum in downtown San Diego, as part of the Naval Aviation Enterprise 2018 Command Master Chief/Senior Enlisted Leadership and Spouse Training Symposium, Nov. 7, 2018. Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Chelsea D. Meiller, USN.

“The good news is, we’ve found that if a sailor understands why they’re doing something, they’re more eager to do it. There is a sense of urgency in our fleet right now. The landscape is changing and we need to be prepared for it. And that’s a huge part of the role of our CMCs and their spouses, making sure every single one of our Sailors and their families understands the threat is real, and that we’re ready to go.” Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

22

The CMC Symposium is just one component of CNAF’s robust leadership development program, started

The Case for Integrating the Tactical Support Unit (TSU) into Fleet Training By LT Eli “Ham” Sinai, USN

HSC-3 at Fallon. Photo by Ray Rivard.

I

n April of 2018, I went on detachment with Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron EIGHT (HSC-8) at Naval Air Station (NAS) Fallon for unit-level strafe and overland training. I planned to complete my Day Overland Special Operations Forces (SOF) grade card in conjunction with our guest pilot, LCDR Jaden Risner, who was in Fallon to complete his Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Program (SWTP) Level IV standardization and evaluation (STAN-EVAL). LCDR Risner is a member of Tactical Support Unit Pacific (TSUPAC), one of two Navy Reserve Units where third, fourth, and fifth tour Selected Reserve (SELRES) and Full Time Support (FTS) Pilots -- usually those who served at Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron EIGHT FOUR (HSC-84) or Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron EIGHT FIVE (HSC85) -- embed with Helicopter Sea Combat Weapon School, Pacific (HSCWSP) to provide training to all HSC squadrons in order to incrementally increase the Navy’s overall capability to support SOF. 23

I was naive about fleet expectations for SOF mission planning, and LCDR Risner challenged me to treat our scenario as if we were in an operational environment. From that point, he threw me into mission planning, nitpicking every detail we would execute on the day of our event. His requests for information covered every factor vital to mission execution. We spent countless hours mission planning, perfecting our routes, fuel, and communications plans, and mission products; moreover, we consistently chair-flew the event to expose our plan’s shortcomings. The day prior to the event, we physically taped up the flight line to represent the terminal area, and LCDR Risner led a walk-through of the Full Mission Profile. Though we lacked external assets, we had a robust opposition forces (OPFOR) presentation provided by NAWDC that forced us to react and utilize the contingency plans we had established during mission planning. Upon event completion, we critically debriefed all lessons learned and areas for improvement. While I had www.navalhelicopterassn.org

FEATURES

in 2002, which includes the Aviation Flag Officer Training Symposium (AFOTS), prospective executive and commanding officer training (PXO/PCO), and the O-5 and O-6 Career Training Symposiums (CTS). All of these leadership events include spouse training. Additionally, CNAF holds an annual Female Aviator Career Training Symposium (FACTS), and has planned a first-ever Junior Officer Career Training Symposium for 2019.

During the symposium, aviation CMCs and SELs also heard from the Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy, Russell Smith, and the Fleet Master Chiefs from U.S. Fleet Forces Command and U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Third Place Winner in the Current Category was the photo “Reaching the Pinnacle” taken by LT Garrett Lukasek, USN.

completed a full Optimized Fleet Response Plan – with all the associated opportunities to train in a variety of tactical environments with both squadron and HSCWSP instructors – I had never felt more prepared to execute an event than with LCDR Risner.

member of the TSU. Not only was it eye-opening tactically but was also extremely beneficial in other areas critical to our profession, such as our discussions about risk management and mission contingencies. This is not a rallying call to lengthen the current SWTP syllabus. Instead, this will supplement the instruction of the Weapons Schools and Fleet Squadrons by providing a wider spectrum of experience, necessary motivation, and community buy-in for our community’s junior aviators.

Integrating the TSU into fleet-wide tactical training has tangible benefits, particularly in the realm of Close Air Support, Personnel Recovery, SOF and Helicopter Visit, Board, Search and Seizure mission sets. But how do we gain the wealth of corporate knowledge offered by the TSUs? Training Officers can easily incorporate the TSU by asking them to lead comprehensive mission planning labs for junior aviators prior to the start of their SWTP progression, assist in day-to-day mission planning, and inviting them to accompany HSC squadrons during Helicopter Aircrew Readiness Program, Air Wing Fallon, and other tactically focused exercises and workups. These mechanisms enable TSU aviators to share their knowledge, and keeps TSU aviators flying outside of HSC-85 in order to maintain their currencies and relevance with their fleet counterparts. At the Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS), TSU aviators can guide Department Heads (DHs) and others returning to the Fleet, improving mission planning readiness and strengthening the cadre of our Squadrons’ Department Heads; lacking the experiences gained from these TSU-led events, Squadron DHs might not otherwise know what they should – or could – expect from their Squadron Junior Officers. As Fleet pilots, we can all benefit from doing an event with a Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

My experience was unique, but it shouldn’t be. Firsttour pilots rarely work with SOF units, and it is difficult to simulate a scenario without being lured into going through the motions of gamesmanship intrinsic to completion of a SWTP grade card. That said, the opportunity to work alongside a member of the TSU provided perspective and comprehension of mission realities. The TSUs are valuable – they have a high capacity to mentor and develop Fleet aviators by introducing them to the methodologies, tactics, techniques, and procedures of HSC-85 and HSC-84. This improves our lethality and warfighting capability, and bridges the gap between rotary wing squadrons and SOF units. Therefore, squadrons should be eager to integrate the TSU into training their junior aviators and Department Heads. Through advocacy of mentorship, mission planning skills, and inclusion on training exercises, we will better fulfill our role in the Navy and when called upon, be ready to carry out any task with tactical excellence.

24

25

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Features Land of the Free, Home of the Brave By AWR1 Joshua Davis, USN

The Bear Dance, performed by members of the Southern Ute Tribe welcomes the bear out of hibernation and the beginning of spring season. The bear symbolizes leadership, strength, and wisdom.

A

WRCS Stanley D. Cox II, USN grew up in Ignacio, Colorado. It’s a small town in the southwestern part of the state, and home to the Southern Ute Indian Tribe. The reservation is approximately 1 million acres, expanding 100 miles from Cortez, Colorado to Dulce, New Mexico. He grew up on the Southern Ute Reservation, although his roots are Navajo and Zuni. His Native blood comes from his mother’s side of the family. Both his grandparents on his mother’s side grew up in New Mexico and moved north to Colorado in the 1930’s. The Navajo reservation spans approximately 10 million acres across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. The Zuni reservation is located south of the Navajo Reservation near Gallup, New Mexico. His family history runs deep there; his uncle John Wellito was even a Navajo Code Talker in World War II.

Rotor Review #143 Winter ‘19

Life on the reservation was pretty ordinary; it was similar to how most Americans that grew up in small towns in the 80s and 90s. Ignacio is a heavily trafficked tourist attraction due to its natural beauty, mountains, rivers, and history. The residents there have their own unique culture, which gives them pride and an identity. From a young age, AWRCS Cox was rooted deep in his culture all the way until he joined the Navy. His mother had 11 brothers and sisters, many of whom married local Southern Ute tribe members. Many people close to him, including his friends, were always surprised when he told them that he was not actually Southern Ute. One of his aunts married Eddie Box Jr., son of the Ute tribe’s ceremony leader. His Uncle Eddie’s father, Eddie Box Sr., was the tribe’s ceremony leader. Although Eddie Box Sr. was not his actual grandfather, he treated 26