Glenn Barkley

Ry David Bradley

Sam Jinks

James Lemon

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran

Alex Seton

Darren Sylvester

Hiromi Tango

Yang Yongliang

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu

FEB/MAR 2023

Editorial Directors

Ursula Sullivan and Joanna Strumpf

Managing Editor

Chloe Borich

Senior Designer & Studio Manager

Matthew De Moiser

Designer Ben Simkiss

Proofreaders

Claire Summers

Millie McArthur

Hannah Sharpe

Production polleninteractive.com.au

Advertising enquiries art@sullivanstrumpf.com or +61 2 9698 4696

Subscriptions

6 print issues per year AUD$120

Australia/NZ $160 Overseas

SULLIVAN+STRUMPF

Ursula Sullivan | Director Joanna Strumpf | Director

SYDNEY

799 Elizabeth St Zetland, Sydney NSW 2017

Australia

P +61 2 9698 4696

E art@sullivanstrumpf.com

MELBOURNE

107-109 Rupert St Collingwood, Melbourne VIC 3066

Australia

P: +61 2 9698 4696

E: art@sullivanstrumpf.com

SINGAPORE

P +65 83107529

Megan Arlin | Director, Singapore

E megan@sullivanstrumpf.com

sullivanstrumpf.com

@sullivanstrumpf @sullivanstrumpf @sullivanstrumpf sullivan+strumpf

Sullivan+Strumpf acknowledge the traditional owners and custodians of country throughout Australia and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and community. We pay our respects to the people, cultures and elders past, present and emerging.

FEB/MAR 2023

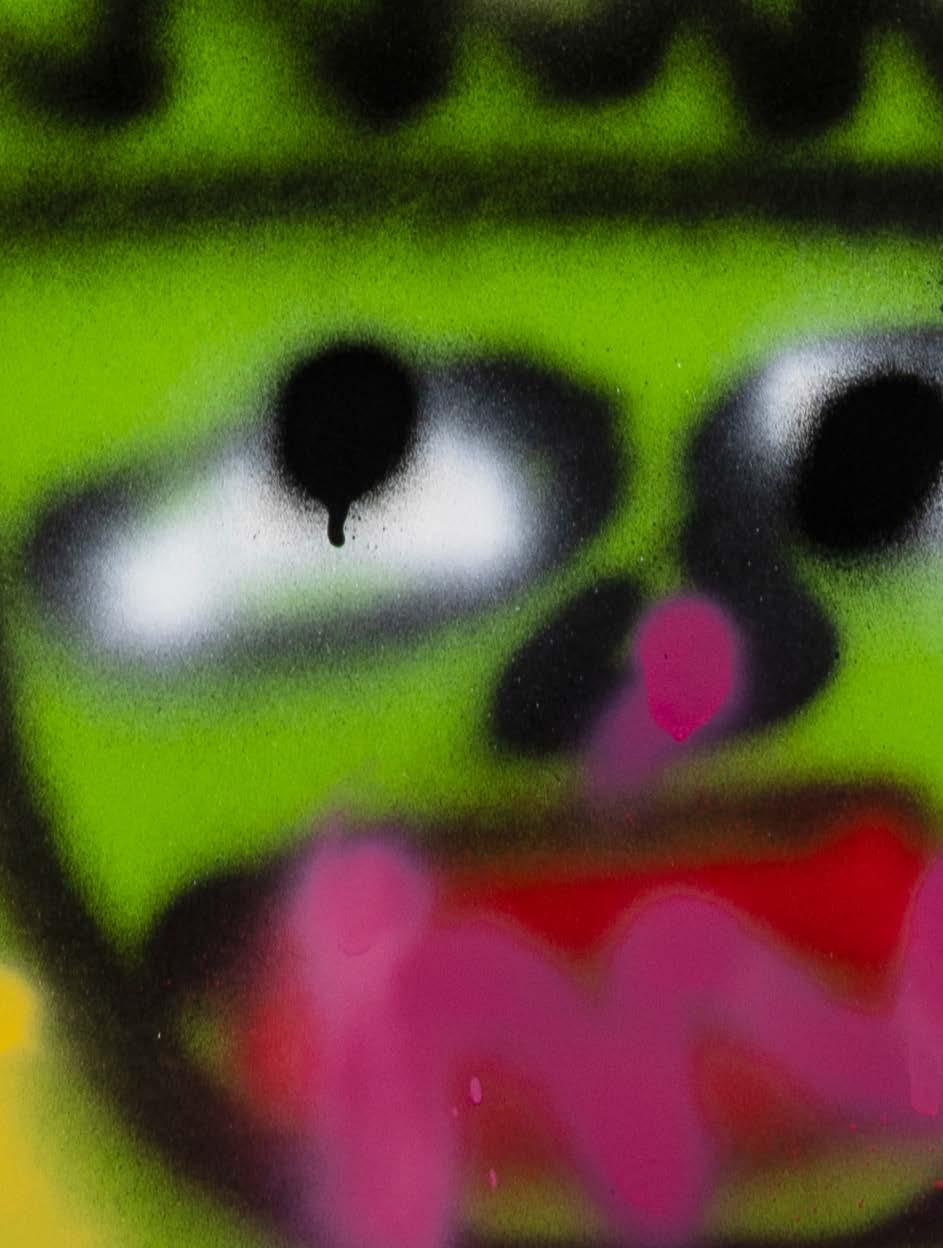

FRONT COVER: Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran Bi Warrior Figure, 2022 (detail). Photo: Mark Pokorny

Julia Gutman, Isn’t it all just a long conversation? , 2022, installation view, Primavera 2022: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2022, donated textiles, embroidery, chains, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, © the artist, photograph: Anna Kučera 4 November 2022 –12 February 2023 Free entry mca.com.au Government Partners Supporting Partner Exhibition Patron Cynthia Jackson AM

2022: Young

Primavera

Australian Artists

Flowing Everywhere and Always Lindy Lee

Open Wed – Sun, 10am – 5pm DST | 2 Mistral Rd, South Murwillumbah NSW | gallery.tweed.nsw.gov.au | tweedregionalgallery

The Tweed Regional Gallery & Margaret Olley Art Centre is a Tweed Shire Council Community Facility and is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

A

Tweed Regional Gallery initiative

26

2023

Lindy Lee Moonlight Deities (detail) 2019–20, installation view, Lindy Lee: Moon in a Dew Drop, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2020, mixed media, image courtesy the artist and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, © the artist, photograph: Anna Kučera Lindy Lee is represented by Sullivan + Strumpf

2 December 2022 –

February

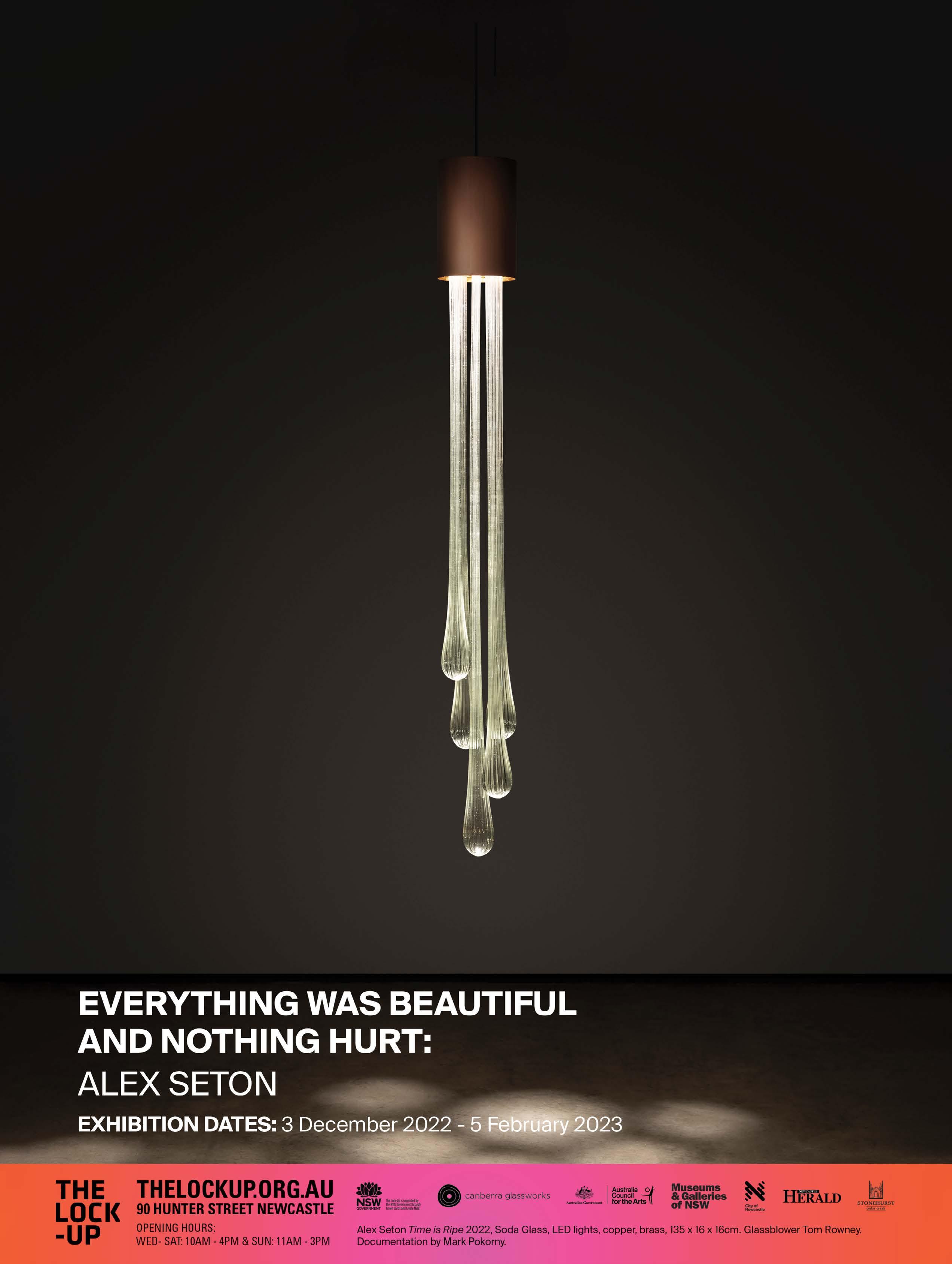

Alex Seton The Amber of this Moment, 2022 (detail) 48 soda glass droplets, copper, brass and 6x1600lm LEDs 185 x 80 x 60 cm

Glassblower: Tom Rowney

Edition of 3 plus 2 Artist’s Proofs

Photo: Mark Pokorny

Alex Seton The Amber of this Moment, 2022 (detail) 48 soda glass droplets, copper, brass and 6x1600lm LEDs 185 x 80 x 60 cm

Glassblower: Tom Rowney

Edition of 3 plus 2 Artist’s Proofs

Photo: Mark Pokorny

New Perspectives

Ursula Sullivan+Joanna Strumpf

As a new year commences so too does our roster of new exhibitions by a medley of formidable artists. After returning to Singapore for the first time in three years to participate in Art SG and S.E.A Focus—both of which were wildly successful—we’re back on home ground and delighted to launch our 2023 calendar with a stellar lineup over February and March.

In this issue, we unveil major solo exhibitions by our cover stars Darren Sylvester 2 Telegenic 2 Die (S+S Sydney) and Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran Undergod (S+S Melbourne). Dr Patricia Jungfer delves into Hiromi Tango’s deeply poignant exploration of grief, loss and longing (S+S Sydney), and Isabella Trimboli explores Sam Jinks’ mesmerising new body of work, which will mark his first solo show in Australia since 2012 (S+S Melbourne). We visit James Lemon’s lightfilled Melbourne-based studio; immerse ourselves in Alex Seton’s glass chandeliers for Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt at The Lock-Up, Newcastle; and enjoy the nostalgic reflections of our Melbourne team in this edition of Quick Curate.

We are also thrilled to announce the first ever solo show of Dhopiya Yunupiŋu, a Yolŋu artist from north-eastern Arnhem Land, whose work looks at the ceremonies and trade paths from the sixteenth century between the Makassan and Yolŋu people. Sullivan+Strumpf Sydney is honoured to present her exhibition in February.

There really is so much to look forward to this year and we can’t wait to share more with you soon.

Happy reading!

Urs+Jo

11

FEBRUARY/MARCH

2023

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Djiḻawurr (Scrub Fowl), 2022 natural earth pigments on stringybark 81 x 70 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

FEB/MAR 2023 67 79 40

Contents

Quick Curate: Nostalgia

James Lemon’s Confections

New Painting: Ry David Bradley

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu: Making History

Glenn Barkley: Aqua Obscurities

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: What Lies Beneath

Sam Jinks: Hope in the Wilderness

Darren Sylvester: The Engineer

Hiromi Tango: Hanamida 花涙 (Flower Tears)

Alex Seton: Everything was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt

Yang Yongliang: Vanishing Landscape

Last Word: Emily Rolfe, C-A-C

13

14 18 24 26 36 46 56 64 74 86 96 106 49

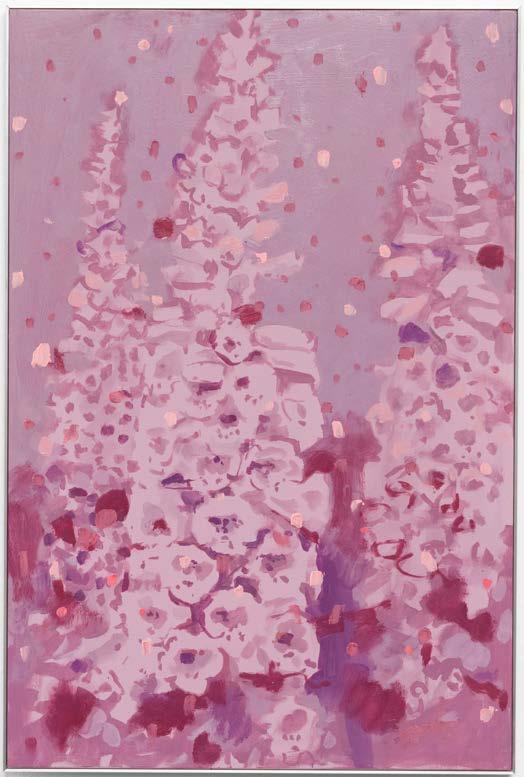

Quick Curate: Nostalgia

Time was an abstract concept when you were a child. Days seemed to last forever, unphased by the pace of the world that existed outside of naïve fixations, like the intrepid journey of a snail across concrete, or the sweet flavour of a thoughtfully selected ice cream. Though as we grow, adult life brings with it the measures and motions of time. Dates are made, moments planned, minutes become valued by their productivity over their spontaneous ingenuity. For this edition of Quick Curate, our Sullivan+Strumpf Naarm/Melbourne team step back momentarily into the slowness of childhood, when time was purposefully squandered and spent enjoying the humble idiosyncrasies of everyday life.

FEB/MAR 2023

“Swirling purples and pinks were the epitome of glamour for me when I was little. Sprawled on sun-soaked lawn, a bit crispy from drought, in a pale pink ballet tutu slugging icy water or a rainbow paddle pop with the whole day stretching in front of you. A perfect day.”

15

Natalya

2021-2022 tufted rug (cotton

adhesive) 130 x 81 cm Edition of 3 plus 1 artist's

Judy Millar Untitled, 2017 acrylic and oil on canvas 140 x 95 cm

Hughes Black Snake! ,

and wool yarn, backing cloths,

proof

Photo: Charlie Hillhouse

Kirsten Coelho Cups #3, 2022 porcelain, celadon glaze 9.5 x 9 cm (each)

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Millie McArthur Gallery Manager, Naarm/Melbourne

Siobhan Sloper Client Manager,

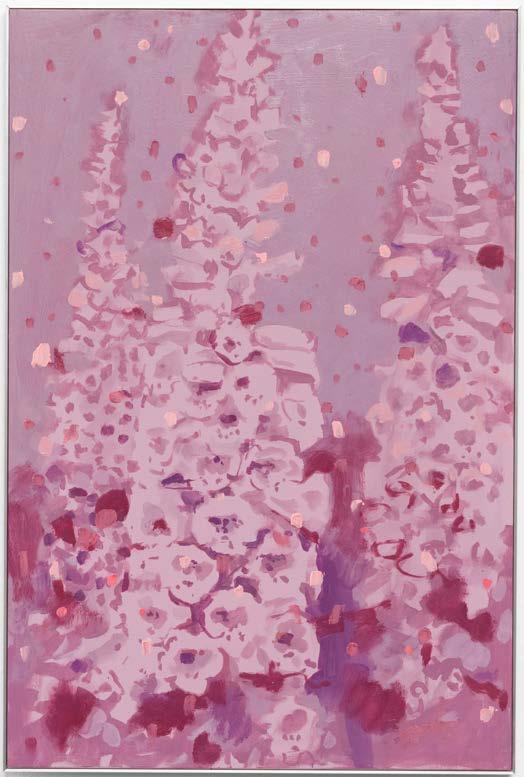

“Many summer afternoons were spent in my parents’ garden planting flowers and chasing bees. Today, the global bee population is declining at an alarming rate. You can help by planting a mix of native flowers in your garden, supporting local Aparists and buying genuine honey. What else would we put on our cornflakes?”

Naarm/Melbourne

Dane Lovett (TOP LEFT) Foxglove 20, 2019 oil and acrylic on poplar panel 60 x 40 cm

60.6 x 40.6 cm (framed)

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Jemima Wyman (TOP RIGHT) Flourish (No.5), 2019 hand-cut photos on paper

132 x 101.5 cm (unframed)

149.5 x 119 cm

Photo: Ed Mumford

Joanna Lamb (BOTTOM) Kelloggs Still Life 2, 2016 laminex on aluminium 70 x 61.5cm Edition of 3

Photo: Nicholas White

Naarm/Melbourne

Dane Lovett (TOP LEFT) Foxglove 20, 2019 oil and acrylic on poplar panel 60 x 40 cm

60.6 x 40.6 cm (framed)

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Jemima Wyman (TOP RIGHT) Flourish (No.5), 2019 hand-cut photos on paper

132 x 101.5 cm (unframed)

149.5 x 119 cm

Photo: Ed Mumford

Joanna Lamb (BOTTOM) Kelloggs Still Life 2, 2016 laminex on aluminium 70 x 61.5cm Edition of 3

Photo: Nicholas White

“Sydney Ball’s Canto evokes feelings of childhood simplicity and playfulness through his use of vibrant colours and clean geometrics—like discovering the planets in first grade. With Kanchana Gupta’s Folded Pierced Stretched the added tactile layer over the blue stripes is reminiscent of coastal holiday deck chairs and beach towels.”

17

Sydney Ball (MIDDLE) Canto VIII, 2003 screen print 77 x 77 cm

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Dawn Ng (TOP) I Will Follow You into The Dark, 2022 residue paintings, acrylic paint, dye, ink, 300 GSM acid-free watercolour paper 120 x 74.5 cm each (2 panels)

Photo: courtesy of Dawn Ng Studio

Kanchana Gupta (BOTTOM)

Folded Pierced Stretched #009: Blue on White /White on Blue, 2021 oil paint skins with silk screen printing, galvanised steel frame, steel eyelets and suspension cable

Photo: Jing Wei

Oliver Todd Gallery Assistant, Naarm/Melbourne

Name Title, Year Materials Size

Photo/ Image Credit

James Lemon’s Confections

Millie McArthur (Gallery Manager, Naarm/Melbourne) visits James Lemon in his Northcote-based studio one sundrenched afternoon in November to talk about colour, sweet treats and the assorted insinuations that may be perceived from his bewitching ceramic creations.

By Millie McArthur

Gorgeous opulence and confronting realities are words that come to mind in the presence of works by James Lemon. Dotting the front entryway of his Northcote-based studio, even while in progress Lemon’s ceramic forms are less, less is more and much more, more is more, with hunks of gold and glazed stoneware sparkling in pools of afternoon sunshine. Sunning herself in the corner is Beatrix, a Collie crossed Jack Russell, whose sweet little face would be instantly familiar to anyone who follows Lemon on social media or wanders past his studio at any given time of day. Lemon professes he loves working in the company of his beloved Bea, and of course his studio assistant of three years, Mali Taylor, who gives me a friendly wave. I step inside the shady relief of the studio and into the buzzing atmosphere of creativity in full swing: Lemon and Mali dart about coiling, constructing, making, and Bea patters around in pursuit of the next best stream of light to resettle herself in.

19

JAMES LEMON, 11 MAY – 3 JUNE 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

James Lemon with Beatrix in his Melbourne-based studio, 2022.

Photo: Melissa Cowan

When initially asked what his least favourite colour is, Lemon deplores the mere notion of despising one, as there is room and necessity for the entire spectrum. He then quickly pivots to admonishing a dark, leeching grey. It mutes and dulls, represses and dilutes. This is not part of Lemon’s ethos, either as a human or within his work. Instead, he uses grey as a way ‘to bite into other colours’. Indeed, Lemon’s works are confections not unlike those my unimpeded childhood brain conjured up when envisioning a Willy Wonka inspired lolly shop or sugary feast. The drool-worthy forms warp in the extreme heat of the kiln, hints of ruby glinting as strawberry jam might ooze out of a hot, sweet doughnut winking with crystallised sugar. Sweet little pearls perched on the lip of a bright yellow pot appear as a dollop of cream might daintily glisten atop a freshly cut scone.

Faced with the hypothetical choice between confectionary sandwiches of either peanut butter and jam, or peanut butter and honey, he decides on PB and jam. Syrupy shades of bold colour win out every time. Gold or silver? Instantaneously he goes for gold. There is something too fascinating, too tantalising, too ethereal about this precious metal. Not only aesthetically captivating, but the history of it as a desired object and the strange

properties it possesses. It feels magical, like it is imbued with something other. And so, when Lemon encases his stoneware in the molten gold, there is a shimmering delightfulness and mysteriousness instilled within each piece.

In the same breath, the visual extravagance of gold that evokes sweet indulgence presents a strong juxtaposition with Lemon's work to divulge the decimation of ecologies and insect life across the globe. At the centre of his practice is an entropy in action, a mode of chaotic energy that is revealed in the twists of the bodies and treacly glazes of his fully realised pieces. A saccharine lightness shines through and collides with the rebellious undertone of everything he creates. Although for the moment, we can sit and enjoy his luscious ceramics as we would a sticky peanut butter and jam sandwich in the studio sunshine with Bea by our side.

For his forthcoming exhibition at Sullivan+Strumpf Sydney, Lemon will turn his focus to abundance. Sinking into what he does best, it will be ostentatious. Stirring, perhaps grotesque. Simultaneously purporting the ancient methodology shared by many species, instinctively creating objects, things we need and break, out of clay.

FEB/MAR 2023

21

James Lemon cockturtle, 2021 stoneware, kiln bricks, glaze, cubic zirconia, mixed media 64 x 67 x 36 cm

Photo: Melissa Cowan

FEB/MAR 2023

James Lemon Mill, 2020 stoneware, glaze and mixed media 21 x 13 x 14 cm

Photo: Melissa Cowan

James Lemon (ABOVE) worm and scraps 1, 2022 stoneware, glaze and gold 35 x 35 x 45 cm

stump plinth, 2022 (BELOW) stoneware, glaze and gold 40 x 29 x 29 cm

Photo: Melissa Cowan

23

James Lemon Phil, 2020 terracotta, glaze and enamel paint

20 x 28 x 12 cm

JAMES LEMON, 11 MAY – 3 JUNE 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Photo: Melissa Cowan

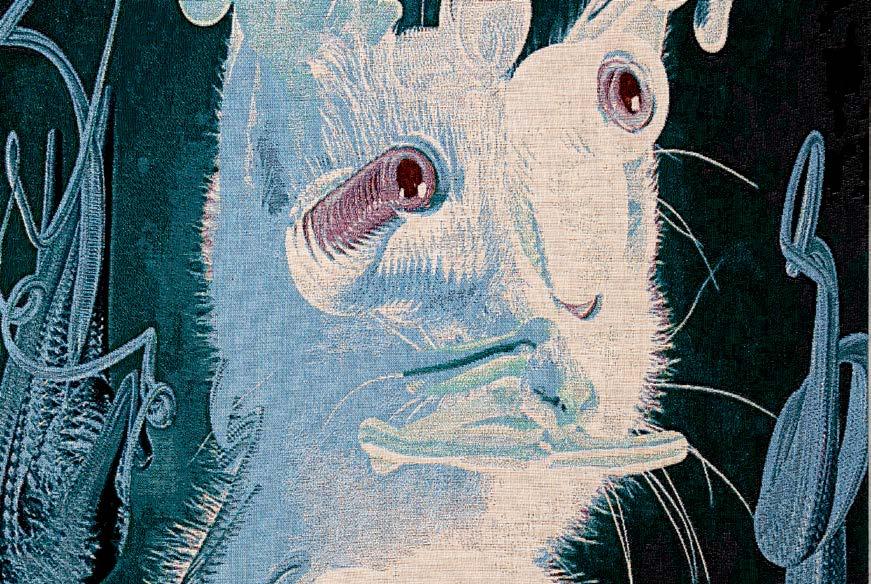

Ry David Bradley New Painting:

By Alana Kushnir

What does painting mean, today? How is painting still relevant in the 21st century? These are the questions that have consumed the art practice of Melbourne-born, Parisbased artist Ry David Bradley for more than a decade.

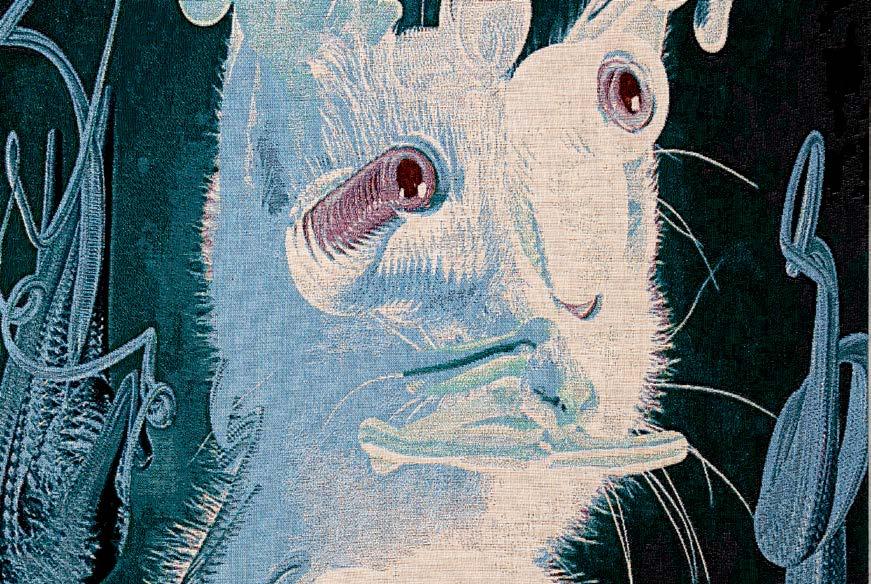

At first glance, the presence of painting in Bradley’s work might be a little challenging to notice. There’s no canvas or paper, no pigments applied by human hand with a bristle brush or a palette knife. Instead, there are digital images printed on synthetic suede. Tapestries are made with a Jacquard weaving machine. And still, every single work of his is about painting—its radical permanence, romantic sensibilities and its continuing pre-eminence in the Western art historical canon.

Many of us have a naïve faith in new forms of technology. We’re always hungry for the latest form of digital storage and the next type of intelligent tools that can make our lives just that little bit easier. But Bradley wants to remind us that it is painting that has stood the test of time. We can still see 17,000-year-old Aboriginal rock art paintings made using iron oxide ochres in the northern Kimberley, Michaelangelo’s sixteenth century frescoes at the Sistine Chapel and Hokusai’s ‘the Great Wave’ ink and colour print on paper from the nineteenth century at The Met in New York. For his graduate show at the Victorian College of the Arts in 2012, Bradley created a series of playful, bright digital images printed on aluminium titled Each Copy May Perish Individually. Each work was paired with an everyday object counterpart—a tote bag, a cap, a USB—on which was the same digital image was printed or stored on. To this day, this experimental sensibility continues in Bradley’s work.

Back in the early days of Instagram, there was a moment in time before an image loaded in its full glory. That anticipative blur became the subject of Bradley’s experiments with printing digital images on synthetic

suede and silk. Shows like Access All Areas in Los Angeles, 2015, Painting More Painting at ACCA in Melbourne, 2016 and Room with a View in New York, 2017 were hallmarks of this period of his practice. Soft, shadow-like forms in vibrant colours acted like new age Rorscharch Inkblot Tests—Bradley was encouraging us to question our ability to make sense of the tech-obsessed world around us.

The year 2018 marked the start of another creative leap for Bradley. He began to trial a weaving technique for his digital images using a Jacquard loom—a 19th century French invention which can create intricate patterns and which kickstarted the automation of textile production. The Jacquard system uses a series of punched cards that encode which thread should be used where. It is considered an important precursor to modern computing—a fact not lost on Bradley. Using a pointillist design ala Seurat and Signac, the subjects of Bradley’s tapestry works are only recognised when standing back and looking from a distance.

At shows such as Transmission at Sullivan+Strumpf in Sydney, 2020, Once Twice in New York, 2021 and in Stockholm, 2021, Bradley fine-tunes this weaving process as well as his image-making tools. He uses his own custom-made digital brushes, which are designed to mimic hand-held bristle brushes. Images of animals and humans are painted by the artist using his iPad screen—he stretches and exaggerates their facial features, and adds gigantic tear drops that spill out of their eyes. There’s more than a touch of existential sadness in these faces.

Bradley’s thirst to evolve his ideas and techniques is never satiated. ‘I like to push forward and try new things while I am at this stage of my career, rather than just do the same thing over and over again’. So, we can reflect on this past decade of his work as a series of necessary experiments— in new forms of painting.

FEB/MAR 2023

RY DAVID BRADLEY, 27 APR – 18 MAY 2023, S+S MELBOURNE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

25

Ry David Bradley

CS1+FR=23, 2023 78 x 58 cm acrylic and inkjet print

on paper

Photo: courtesy of Ry David Bradley Studio

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu: Making History

History comes in many shapes and forms. We are tuned to history, which comes in books and ruins. Australian history is more intangible. In this case, it comes in epic song poetry and shards of pottery, which is not necessarily the history we’ve been told.

By Will Stubbs

27

DHOPIYA YUNUPIŊU, 28 FEB – 24 MAR 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu with Nyumuminy (a nickname for Shorty), 2022. Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

Underpinning Dhopiya Yunupiŋu’s first solo exhibition is the historical fact that European people were not the ‘first contact’ with Australians. There is significant archaeological evidence of this, including the important rock art site at Djulirri in the Wellington Range of Northwestern Arnhem, showing a yellow Makassan prau (boat) lying under a beeswax ‘snake’. The snake has been shown to have been laid down no later than AD 1664.

At the exhibitions heart, is an acknowledgement and appreciation of the ceremonies and rituals associated with the annual visits by Indonesian praus over hundreds of years. Makassar fishermen arrived each December to camp along the Arnhem Land coast to gather trepang (sea cucumber) for trade with China. People in China enjoyed eating trepang and believed that it also increased their sexual desires. By the mid-1800s, one-third of all the trepang eaten in China (about 900 tonnes) came from the Arnhem Land trade. Trepang is still used in China as food and medicine.

These sailors and gatherers of trepang from coastal waters, caught the seasonal winds back and forth from what is now known as Sulawesi. Yolŋu know this place as Maŋgatharra. During the trade, Yolŋu would visit Sulawesi and sometimes stay. Similarly, Makassan sailors would sometimes remain in the Top End, known as Marege. The relationship they had with the Yolŋu was amiable and productive. The trade was not just sourcing the product but a complicated processing technique of gutting, boiling, burying in the sand for a period and then drying in racks or smoking in small huts. Yolŋu were involved in all aspects of this industry as well as supplying the camps with firewood, food and water. The relationship extended to shared spiritual expression.

Until the turn of the last century the annual visitations of the Makassanese to the Top End shores of Australia were a lynchpin of the Yolŋu economy and society. These visits were banned by the newly formed Australian Government from 1901.

Dhopiya's father Muŋgurrawuy (Gumatj clan) was familiar with Makassan culture and drew a representation of Makassar City for the anthropologist Ronald Berndt in 1947. It is the stories handed down from her father that Dhopiya refers to directly.

“Dhopiya's father Muŋgurrawuy (Gumatj clan) was familiar with Makassan culture and drew a representation of Makassar City for the anthropologist Ronald Berndt in 1947.”

FEB/MAR 2023

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Darripa djäma (Processing Trepang), 2022 pigment on terracotta ceramic 41 x 36 x 36 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

29

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Bayini, 2022 natural earth pigments on stringybark 100 x 71 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

Many Gumatj places are connected to the trade including Maṯamata, Bawaka, Gunyuŋara,Galupa and Dhanaya. Epic Gumatj song poems reference Galiku (Cloth), the anchor, the Djiḻawurr (Scrub Fowl—known to frequent jungle beachside areas common to these Marŋarr) and the Tamarind, steel knives, märrayaŋ (guns), pillows, tobacco, flags, sail, cards, money, Djambaŋ (tamarind trees), Djolin (musical instruments) and Ŋanitji (alcohol).

The Gumatj homeland on Port Bradshaw is Bawaka but also known by its Makassan name Gambu Djegi, now understood as a translation of ‘Kampong Zikir’, Bugis for ‘a sacred village’. This place is an ongoing source of pot fragments buried in the sand which come to the surface after the Wet Season. The pots originated with the Torajan ethnicity rice and corn farmers who used the clay from their rice paddies and then fired them with the husks at the end of the harvest. They were traded to the Bugis seaman in their praus who used them to carry their supplies of water and rice.

The pots at Bawaka are the result the end of harvest ritual to smash the pots enshrined in songlines. The Makassans would hold a big feast and share their spare supplies prior to loading the ship with dried and processed trepang. The songlines end with the revellers 'butulu badaw!' (smashing the pots) at the end of the party. Bawaka is also associated with the female spirit Bayini who still inhabits this place. She may have been murdered here. She is a trickster who targets single men and covets gold.

Several of Dhopiya’s nieces visited Makassar in 1988 and met the elderly daughter of a Yolŋu woman who had followed her partner back to Maksassar but had been barred from returning home due to the 1901 embargo. From 2015, the renewal of the relationship intensified and the pots used in this exhibition were sourced from Sulawesi, from the Torajan artisanal tradition.

31

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Galiku Buŋgul (Cloth Dance), 2022 natural earth pigments on stringybark 76 x 65 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

FEB/MAR 2023

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Marthaŋa - Prau (Macassan's arriving), 2022 natural earth pigments on stringybark 49 x 98.5 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

33

As the seasons of the year ran the same ageless cycles, so did the Makassan visits. Yolŋu sacred songs tell of the first rising clouds on the horizons—the first sightings for the year of the Makassan praus’ sails. The grief felt at the time of Makassan trepangers returning to Sulawesi with Bulunu (the S.E winds of the early Dry season) is correlated with the sunset. Djapana means ‘sunset’ in Yolŋu matha and ‘farewell’ in Bugis. The red sails of the Praus mirror the pink sunset clouds. The death of the Sun at day’s end equated in song with the grief at the passing from life of a member of the clan. The return of the Makassans with Luŋgurrma (the Northerly Monsoon winds of the approaching Wet) is an analogy for the rebirth of the spirit following appropriate mortuary ritual. This also correlates to the songs of the reborn morning Sun as it rises.

These handed down stories, poems and songs, speak of a centuries old economic and family history that surpasses Western experience, forming an integral foundation to Yolŋu people, and the subjects of the work by Dhopiya Yunupiŋu.

FEB/MAR 2023

DHOPIYA YUNUPIŊU, 28 FEB – 24 MAR 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

“Yolŋu sacred songs tell of the first rising clouds on the horizons—the first sightings for the year of the Makassan praus’ sails.”

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Djambuŋ (Tamarind trees), 2022 pigment on terracotta ceramic 39 x 46 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Djambuŋ (Tamarind trees), 2022 pigment on terracotta ceramic 39 x 46 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

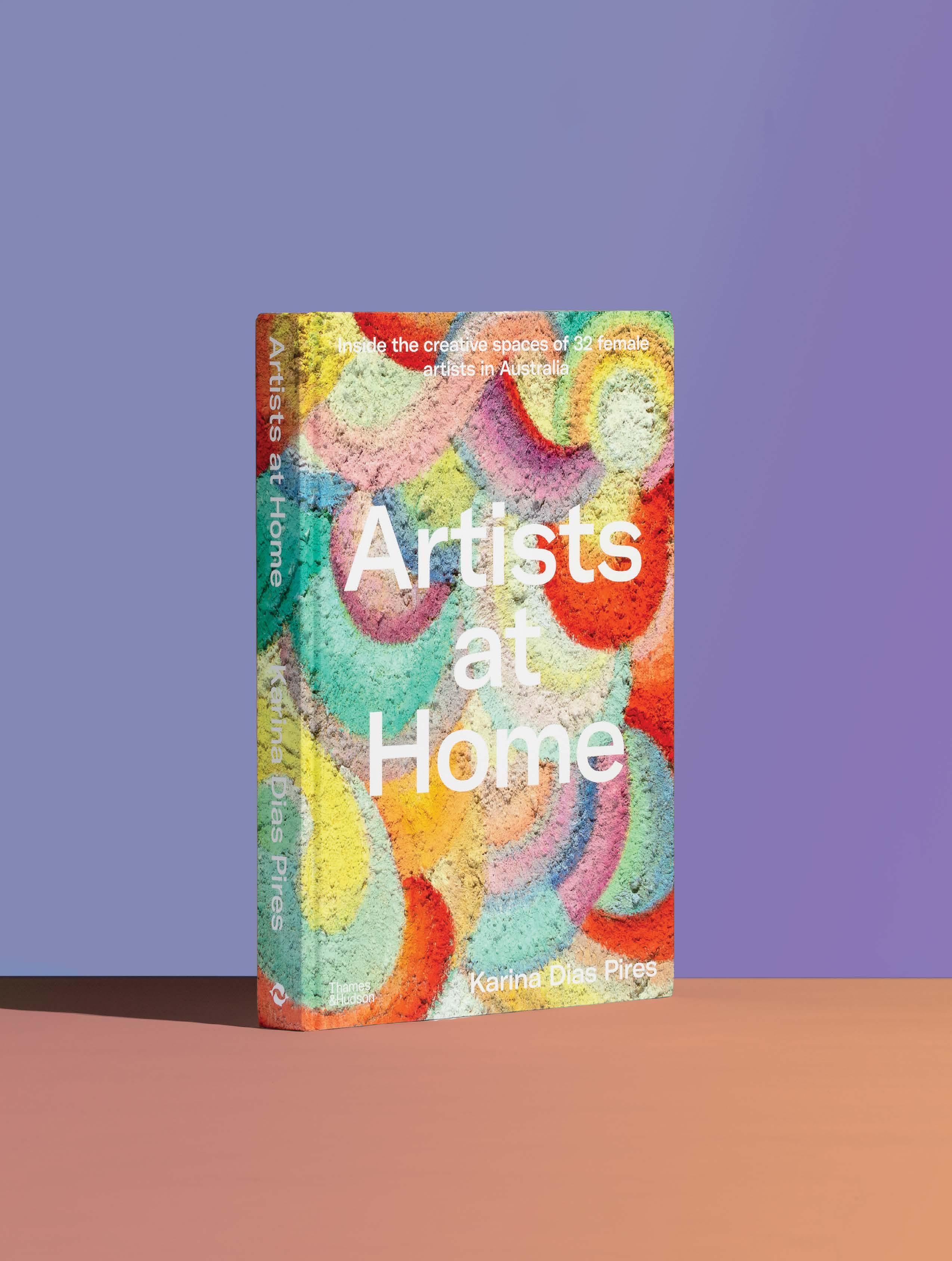

Glenn Barkley: Aqua Obscurities

What do we choose to keep? What do we choose to forget? Brooke Boland speaks with Glenn Barkley about his exhibition at Shoalhaven Regional Gallery, Plant Your Feet, which questions how history is written and by whom.

By Brooke Boland

FEB/MAR 2023

YOUR FEET, 10 DEC – 28 JAN 2023,

+

ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO FIND OUT MORE

GLENN BARKLEY, PLANT

SHOALHAVEN REGIONAL GALLERY

EMAIL

earthenware 17

15

Glenn Barkley Fern Vase, 2022

x

cm

Photo: Jules Boag

Grouping of Glenn Barkley ceramic vessels, 2022.

Photo: Jules Boag

Grouping of Glenn Barkley ceramic vessels, 2022.

Photo: Jules Boag

“It’s about creating new objects and thinking about obscure histories and things that maybe only locals might know about.”

At the centre of Glenn Barkley’s Plant Your Feet exhibition at Shoalhaven Regional Gallery sits a house invitingly called The Wonder Room. Clad with over 800 clay tiles, it’s the work of many hands, children and adults from the Shoalhaven, who have made one tile each. If you look closely, you’ll find a dinosaur somewhere. I know this because it’s what my four-year-old chose to draw under the guidance of artists Cita Daidone and Penny Craig when we stumbled on the project at our local shopping centre. My son sat down in serious and joyful concentration and drew something he loved. What you won’t see when you look at the house is how he hasn’t stopped making things out of clay ever since. How many others—children and adults— went home and made something for themselves? As an example of engaging locals in artmaking, this would be its own measure of success.

When I meet Barkley at his studio just north of Berry, stacks of these tiles are waiting to be fired. ‘There’s still so much to do,’ he says. He continues to glaze small clay shells in aqua blue as we talk. He points out a new work waiting nearby on a crowded shelf; a small puckered vase with a striking blue-black panther. If you’re a local, you know the story of this panther, which has been reported a few times over the years. In the Panther Archives invented by the artist, Barkley attributes an account to Macca

Wardle: ‘It was late, I’ll be honest I’d had a few beers but thought, oh yeah, I’ll just cross that old bridge and get to the pub for a couple of sneaky ones before heading back to the van—that’s when I saw something just in the bushes near the museum with what looked like a fox hanging from its mouth—it was so big the fox looked like a rat! It looked up and for a moment we locked eyes—that panther, I know what it was no matter what Steve said later. I swear it winked and then whooshka-goneski…. Fuck Steve anyway, everyone knows he's the one full of shit’(sic).

Barkley delights in local mythologies, which are reflected throughout Plant Your Feet. ‘It’s about creating new objects and thinking about obscure histories and things that maybe only locals might know about,’ he says.

41

Grouping of Glenn Barkley ceramic vessels, 2022.

Photo: Jules Boag

The exhibition includes new work by Barkley as well as paintings and objects from local museums and regional gallery collections that feature the Shoalhaven landscape. Importantly, the exhibition includes work by First Nations artists from the region, including Ben Brown, Peter Hewitt, and Julie Freeman, among others, as well as shell work by Esme Timbery. Together with Barkley’s large and small ceramics, these works create a dialogue that acknowledges First Nations sovereignty as the foundation of place in this exhibition—where we literally have planted our feet, in many cases. A large roundle by Barkley spells out a line borrowed from poet Judith Wright to drive this point home: ‘I was born into a coloured country’.

Barkley’s inclusion of Wright’s poetry is reflected through the lens of Australian historiography, itself inspired by historian Anna Clark’s new book Making Australian History, which questions how history is written and who gets to write our past. Plant Your Feet stages Barkley’s own consideration of who is represented in local accounts and what stories are kept through practices of curation and collection. ‘What do we choose to keep? Why do we keep it? What do we choose not to keep? What do we choose to forget? What are the actual interesting stories about the region that you can't see?’ These are the questions that really interest him. ‘Like draining swamps,’ he adds. ‘Draining swamps is a key part of history in the Shoalhaven and no one ever talks about it because it's so unsexy,’ he laughs.

Barkley himself grew up in Sussex Inlet and so knows much of the local lore and landmarks, but the project has taken his understanding to another level. ‘I grew up here, but I never really thought about the history of the place very much. It's funny how you can live here for so long and not really think about those things. Especially in a place like the Shoalhaven where First Nations culture is so important. This [region] is a first contact site as well, which I don't think people really acknowledge’. He spent time revisiting the objects held at local museums such as Berry Museum and Tabourie Lake Museum, some of which he first visited as a child.

Outside of the dry history books of the region there’s more to be found in oral histories, artworks, and literature by people from the Shoalhaven, such as the late Frank Moorhouse who grew up in Nowra. ‘It's not rewriting history; it's just thinking about the past and how what has been written could be wrong,’ Barkley says. After all, everyone knows Steve is full of shit.

FEB/MAR 2023

FEET

10 DEC – 28 JAN

TO FIND OUT MORE

“It's not rewriting history; it's just thinking about the past and how what has been written could be wrong.”

GLENN BARKLEY, PLANT YOUR

,

2023, SHOALHAVEN REGIONAL GALLERY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM

43

Glenn Barkley

Red Rocket with stars and moon, 2022 earthenware

27.5 x 11 cm

Photo: Jules Boag

Installation View: Glenn Barkley Plant Your Feet, 2022.

Photo: Jules Boag

Installation View: Glenn Barkley Plant Your Feet, 2022.

Photo: Jules Boag

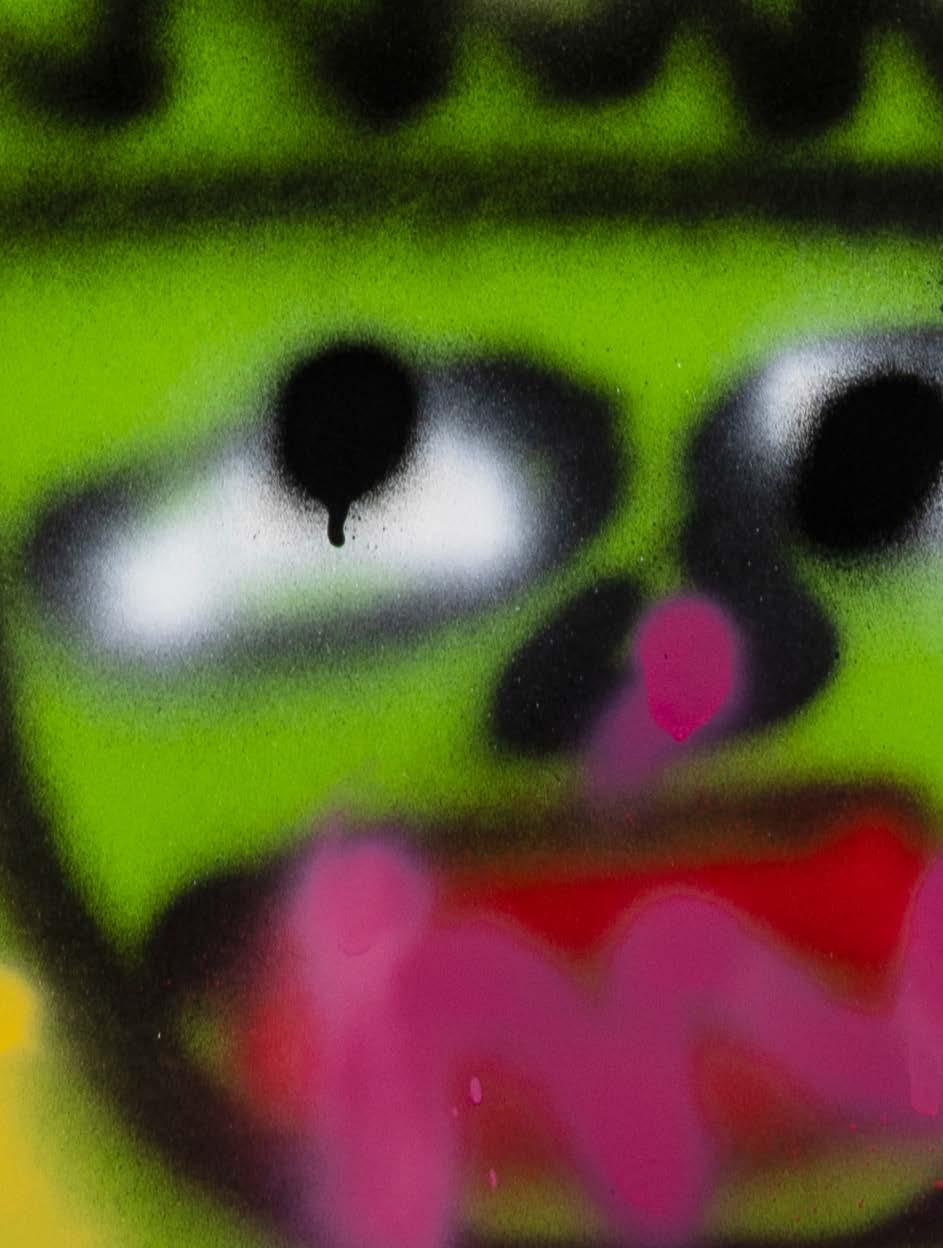

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: What Lies Beneath

Originality pulsates from Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran's at once joyful and imposing forms. In his first solo exhibition at Sullivan+Strumpf’s new Melbourne gallery, Ramesh explores histories of iconoclasm with an undertow of humour.

By Anita King

47

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, 2023.

Photo: Mark Pokorny

RAMESH MARIO NITHIYENDRAN, UNDERGOD, 16 MAR – 22 APR 2023, S+S MELBOURNE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Fascinated by the erasure, destruction, and theft of cultural icons, he stares deeply at what lies behind the scratched-out faces, missing limbs, and displaced artefacts of a global past and how these can be reframed to help guide a path forward. In one of our conversations, Ramesh reflected that the ‘preservation and display of fragmented figures in various museum collections around the world have always struck me. The headless, limbless deities (or sometimes effigies) whose provenance is unclear, encourage me to consider the language and ethics of what may be termed faith-based collections. I’ve always gazed at these fragmented figures and imagined possibilities of regeneration. In 2023, a time of rising global nationalism, what kinds of imagery could gesture to cultural plurality?’

Ramesh’s ecstatic vision emerges from his fascination with the human figure and its representations through histories, across cultures. He draws upon his own cultural experiences, ideas of idolatry and worship, and a fascination with South Asian vernacular to create a distinctive figurative language. He states, ‘I’m interested in syncretic languages specific to South Asia. The way Hindu, Buddhist, and even Christian imagery pollinated various histories makes me think deeply about the plurality at the centre of what we consider regionally specific dialogues’. After arriving in Sydney with his parents as a Tamil refugee in 1989, he spent his early years considering familial practices of Hinduism and Catholicism. Within these very different spheres of worship, he became fascinated by the contrast and similarities of figurative representation, paving the way to an extensive body of work dissecting, abstracting, and reframing the body.

In person, Ramesh’s physical presence is unmistakable. Like his sculptures, he is statuesque and lively; his quick laughter ruptures and lights up the room. His fashion

sensibilities are remarkable. He’s a master of mixing saturated colours and clashing prints, designer clothes and Crocs with platforms higher than you’ve ever seen. He is also industrious, focused, and articulate; a polymath working with confident intention and a lively sense of humour. His works are expressive and intuitive, but also the result of a considered process involving a high level of research, material understanding, and social and cultural awareness. I rarely see him without a tool in his hands, whether a posca pen, carving implement, iPad, or whiteboard marker. He is always poised to make notes, a quick sketch, or add detail to wet clay. He fills diaries with drawings that become references and inspiration for new works. His autographic gestures are fast, fluid, and uninhibited, and he never second guesses a line, sure in his own well-developed aesthetic language.

With fragments of sculpted body parts and curious heads waiting in the background of our zoom call, Ramesh described his compositions. ‘Many of the works in this exhibition have been crudely formed. The torsos, heads, and votive props have been built separately and visibly pieced together in my studio in ways that are hopefully aesthetically and even philosophically unexpected. They might seem a bit ugly, but I’m not interested in making pretty things’. His towering clay totems are created like a game of cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse). You may have played this game yourself as a child; the first player adds a head and then folds the paper over, the next person adds a torso without knowing what the head looks like, and so on. From here, a strange, comical, and surreal character is born. For Ramesh, this fantastic figurative game births timeless polymorphic beings, draped and adorned, nourished by historical iconography and contemporary image culture.

FEB/MAR 2023

67.5

19

Edition of 3 + 2 Artist's Proofs + 1 unique kinetic edition

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran Warrior Figure, 2022 bronze sculpture on custom made spray painted mild steel plinth

196 x

x

cm

(includes motor)

Photo: Mark Pokorny

“He’s a master of mixing saturated colours and clashing prints, designer clothes and Crocs with platforms higher than you’ve ever seen.”

49

FEB/MAR 2023

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran

Warrior Figure , 2022 (detail)

Photo: Mark Pokorny

The use of unglazed terracotta further reveals his skill at breathing life into the inanimate. These pieces have a distinct texture, with fingerprints visible on the surface; the hands that made the work are plain to see. Ramesh told me, ‘I’m newly interested in histories of unglazed terracotta. There is something timeless and promiscuous about the register of these surfaces. The almost primordial sensibility of fashioning or reflecting life from this primary material makes me feel connected to makers and artisans who were working with their hands, earth and fire thousands of years ago’.

Fascinated by the hands and craft that construct our material world, Ramesh is not interested in slick outcomes but rather in the personal and the animated. His works are sentient, anthropomorphic avatars. Some are multilimbed and predatory, and others are just heads without bodies. Each lively character has at least one face; some have many of varying proportions and symmetry, often with expressions resembling emojis (Face with Tongue, or the Miley Cyrus Tongue Face). I imagine them as a grand army of shapeshifters, eclectic misfits, and time travellers, looking to the past and future, to different cultures and heritage, to a place where diversity is unremarkable. I sense that they come to life when the doors are closed; it's a party I'd like to attend, but I'm not sure I'd be welcome.

Ramesh loves snakes, and you’ll always notice a rubber snake or two embedded somewhere in his works. I don’t like snakes; in fact, they terrify me. But I love how wholly and frequently they shed their skin, making room for new growth and leaving parasitic baggage behind. This is precisely the shock and drama that a sculptural object needs to announce itself in an already crowded world. It’s something that Ramesh knows and understands; his work has a persistent and comedic drama. Considering both the object, and the negative space around it, he consciously installs his work to influence how an audience might experience it. His installations will stop you in your tracks, surprise you, and make you wonder what world you have entered. Simple mechatronic animation and LED rope lights that create dramatic air sketches, unite technology and primordial sculptural techniques in a futuristic exploration of the elements. Earth, fire, air, and water, enter electricity in place of aether.

51

FEB/MAR 2023

bronze sculpture on custom made spray painted mild steel plinth

181.5 x 95 x 52 cm

Edition of 3 + 2 Artist's Proofs + 1 unique kinetic edition (includes motor)

53

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran

Bi Warrior Figure, 2022

Photo: Mark Pokorny

His show culminates with a new series of highly patinated, polychromatic bronze works. Using an ancient lost wax technique—with origins tracing back to the Chola dynasty in ancient India—the process maintains extraordinary detail and enables an exact rendition of the original clay sculpture. I visited the Mal Wood Foundry in Melbourne as these new works were being cast; the scene was dramatic and sensorial. Molten bronze bubbled in a crucible atop a roaring fire, steam filled the air each time the lid was lifted, and a pungent metallic odour permeated the room, the noise of polishing and patination thundered in the background. It was a thrilling display of material transfiguration, harnessing the power of fire and ancient techniques.

Bronze monuments in Western contexts have often depicted victorious white males, celebrating a scarred and violent history of conquest and colonialism. The six bronze warrior and guardian figures presented here are in vital contrast. They preside fluidly over the beginning and the end, reaching through time and space, poised and ready, protectors of icons. They are elaborately embellished, abounding with hidden surprises that upend expectations and keep you looking. Here, a durian is cast as a smiling, armoured handbag, a shell is a nipple, a cocktail straw is a penis, and a figurine is buried teratoma-like in a shoulder. While a playful absurdity and humour draw you in, something else begins to unravel. Something more unattainable and uncomfortable, or is it otherworldly awe? His works sit at intersections and leave me with many questions. Is it a smile or a menacing grin? From the past or the future? Synthetic or organic? Male or female? They exist quite happily between dichotomies and uncertainty is part of what makes them so successful.

Working on a single plane of movement, Ramesh has developed his capacity to animate by integrating simple motion-sensing animatronics into two large, Janus-like bronze sculptures (Warrior Figure and Bi Warrior Figure). Encountering these rotating heads is an unexpected and delightful surprise. Ramesh explains, ‘I wanted these large sculptures to come alive with the introduction of industrial technology. It’s another nod to the mixing of time periods, languages and visual registers in my work. There is an almost crude cartoon-like demonic sensibility to the kinetics’.

With these new works, Ramesh forges an unvarnished polychromatic unity of global traditions and aesthetics by mining the fertile ground between contrasting cultural and historical identities. He seeks to uncover what lies beneath the surface of disparate pasts, using centuriesold processes to sculpt global narratives. From the ruins of cultural artifacts comes a new body of work with eyes firmly set on an open and radical future.

“While a playful absurdity and humour draw you in, something else begins to unravel. Something more unattainable and uncomfortable, or is it otherworldly awe?”

FEB/MAR 2023

Installation View: works by Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, 2022.

Photo: Mark Pokorny

RAMESH MARIO NITHIYENDRAN, UNDERGOD, 16 MAR – 22 APR 2023, S+S MELBOURNE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Sam Jinks: Hope in the Wilderness

“A soul can lead, fight and kill; in the sketchy rain there, but you can’t kill where we’re dead. That’s the best thing no one has any power.”

Transfixed by the mysteries of destiny and the instability that governs our lives, Sam Jinks has created a beautiful and blistering exhibition that reflects on our own era of doubt and alarm.

By Isabella Trimboli

57 Work in progress

2023.

in Sam Jinks studio,

Photo: courtesy of Sam Jinks Studio

SAM JINKS, HOPE IN THE WILDERNESS, 18 FEB – 11 MAR 2023, S+S MELBOURNE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

– Alice Notely, The Sea

A woman stands next to a large wooden wheel, pulling its lever. The wheel spins freely. The woman is pleased—her expression conveys glee, haste, and total abandonment. Sometimes her eyes are veiled, and she is shielded from the wreckage caused by her wayward navigation. The victims of her ruin are men, women, and kings, whose bodies cling desperately to the wheel, but whose efforts are in vain. In due time, some will topple off, lost to the whims of chance and providence.

This is the Rota Fortunae—known in modern parlance as the wheel of fortune—which appears again and again throughout medieval literature and art. The woman is Fortuna, the goddess of fate, ruling with fickleness and precarity. She is sometimes, but not always, a stand-in for God, doing the work of dictating the course of lives in his absence. In Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, fortune is the theme that runs throughout many of the tales told by the group of young women and men, who have come to a secluded Florentine villa in an attempt to outrun their own bad luck: the bubonic plague. But the stories recounted all deliver a unified, scathing truth: that the only thing one can be certain of is the cyclical nature of life and death.

In Hope in the Wilderness, artist Sam Jinks is transfixed by the mysteries of destiny and the instability that governs lives, crafting sculptural works that reflect our own era of doubt and alarm. This is an exhibition beautiful and blistering in equal parts, full of objects that are haunted by decay, but are also pervaded by the possibility of renewal. While many of the sculptures deal in physicality, with mercurial precision—saggy skin, sinewy bodies, skulls newly stripped of flesh—they are not without questions of the mind. Permeating each of these works are ideas about faith’s fragility and how consciousness may transcend the limitations of the body.

Jinks has situated the exhibition around the idea of Rota Fortunae. One work sits at the centre of the gallery, while the other sculptures orbit it. This central figure is a reimaging of Bernini’s Corpus, a life-size bronze sculpture by the Italian master, where the crucified Christ stands suspended, arms outstretched, devoid of the wooden cross that held him. Jink’s figure is similarly elevated and

“This is an exhibition beautiful and blistering in equal parts, full of objects that are haunted by decay, but are also pervaded by the possibility of renewal.”

alone, floating in the gallery space. Below, is a pool of still water, inverting the sacred visual. The accouterments of religious iconography have been stripped back to their elemental components, so all that we are left to face is a dead body, that offers only the starkest truths about affliction and redemption. Jink’s sculptural practice, hyperreal and full of intricate detail, often creates the impulse to get up close and inspect. But the figure’s raised stature and pool of liquid create a gulf of distance between the object and the spectator, mimicking how belief requires a submission to the unreachable and ineffable.

To yield to forces beyond control or order, to accept unruliness, has become a more probing question in the spectre of plague and environmental turbulence. There has been a push to scrub clean the stains of the past few years, to pick up where we left off, and move into the future. But this future is blurred, fluctuating, and laced with uncertainty. There is no going back to the time before this collective crisis, and we must contend with the fact that the truths we have previously pushed into the far reaches of the mind have swung back to the centre of our lives. As the psychoanalytical thinker Jacqueline Rose recently wrote, ‘In the midst of a pandemic, death cannot be exiled to the outskirts of existence. Instead, it is an unremitting presence that seems to trail from room to room’.

FEB/MAR 2023

59

Work in progress in Sam Jinks studio, 2023.

Photo: courtesy of Sam Jinks Studio

FEB/MAR 2023

Works in progress in Sam Jinks studio, 2023.

Photo: courtesy of Sam Jinks Studio

61

To think about death and decay is often disregarded as a morbid inclination or an indulgence in doom. But Jink’s work refutes this narrative. Instead, these pieces of corporeal debris and decline offer comfort, a kind of consolation. In times of darkness and deprivation, in the ashes of the deceased, creation continues. Take the work Beast of the Isle of Bags where the remnants of a rabbit, a skull, is housing two snails, who are possibly deriving sustenance from its marrow. Sculptured with care and rigor, these mollusks offer a lesson in primordial resilience—how it might be good to move slowly in the world and retreat when needed.

Then there is Jink’s tableau of innocence and experience: a newborn baby, freshly out of the womb, who is being clutched by an elderly figure. It is impossible not to gaze at the person’s hands—mottled with purple, creased with lines, rendered frail—that seem to bare the marks of every movement and ache of a long existence. This work is a dual celebration: of new life, soft and fleetingly undisturbed. And of the life that has come before it, coarsened and weakened by time, coming to its inevitable end.

63

SAM JINKS, HOPE IN THE WILDERNESS, 18 FEB – 11 MAR 2023, S+S MELBOURNE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Work in progress in Sam Jinks studio, 2023. Photo: courtesy of Sam Jinks Studio

Darren Sylvester: The Engineer

Through photography, construction—and arguably a little bit of magic— Darren Sylvester spins a tale larger than himself, larger than the physical works, entering us into the realm of dreams and stars.

By Angela Garrick

65

Darren Sylvester in the studio, 2022.

DARREN SYLVESTER, 2 TELEGENIC 2 DIE, 23 MAR – 22 APRIL 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Photo: Darren Sylvester

When Dorothy and her friends stumble upon the Emerald City after their long journey, their quest to meet the great and powerful Wizard of Oz is realised. He appears to the travellers as a larger than life, explosive, telegenic delight; inducing enough awe to form a stutter. His face, engorged and angry, screams in sync with pyrotechnic flames. Toto explores the Great Hall and its surroundings, while Oz exclaims to ‘Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain’. Behind the curtain reveals the ‘real’ Oz, a small in stature, humble man who wished to appear elongated, powerful; perhaps in a way like most of us. This enigmatic scene encapsulates so well the role of the artist, who spins a tale larger than life, larger than themselves.

Darren Sylvester is an artist who works across set design, construction, furniture and a very cinematic style of photography. This combination of such specific disciplines conjures thoughts of the artist as Engineer, akin to Oz; somewhat shrouded, twisting knobs, hammering and drilling into the night. Who is he? He is generating smoke and mirrors, and in turn a little bit of magic. He manufactures scenes and worlds, in the hope of ascertaining meaning, humour, and comfort.

The term telegenic pertains to a charismatic moving image portrayal of a person. Could a person be enigmatic on film but perhaps not elsewhere? Sylvester’s 2 Telegenic 2 Die opens up a considered discussion of this 21st century conundrum, asking if the power of the image can incite the everyday object to stray far from reality. The show asks how closely cinematic memories are immersed within our own, and why performative culture elicits such enduring wonder and curiosity.

Landscape Architect Dean MacCannell reflects that, ‘The current structural development of society is marked by the appearance everywhere of touristic space. This space can be called a stage set, a tourist setting, or simply, a set depending on how purposely worked up for tourists the display is'. The construction of Sylvester’s elaborate sets for photographs is reminiscent of a touristic desire, an expectation to see something, and to be wowed, just as you had imagined. To be Telegenic.

FEB/MAR 2023

“This combination of such specific disciplines conjures thoughts of the artist as Engineer, akin to Oz; somewhat shrouded, twisting knobs, hammering and drilling into the night.”

67

lightjet print 160 x 120 cm Edition of 3 plus 2 artist’s proofs

Darren Sylvester Body Be a Soul #1, 2022

Two series in this show, Made up in the Vanity and Body Be a Soul play between both (self) infatuation and (viewer) voyeurism. We, the viewer, get to see what we usually do not, an in-between moment. In this case, the act of getting ready for an unknown performance, and a performer glancing into a mirror, the look is reminiscent of the hall of mirrors in Return to Oz, where one cannot escape multiple copies of their own image.

Star Machine focuses attention on an everyday and utilitarian object—the staircase—and finding that small line that departs it into the realm of the absurd; the fantastical. The resulting photograph depicts stairs leading up into the universe, surrounded by a starry void. You don’t want to climb ‘too high’, as to ascend would be to enter the realm of stars. To step down is to descend to an unknown depth, the netherworld, or onto the everyday, human level. Micky Avalon’s rendition of Beauty School Dropout in Grease (1978) takes place on a perfect white staircase, and as he descends, he calls upon Frenchie to change the direction in her life. Staircases are often a conduit for change, indicative of glamour, escape, and for movement. Star Machine presents an uncanny match to the staircase used in Powell and Pressburger’s 1947 film A Matter of Life and Death. These stairs aptly connect earth to the afterlife, representing true limbo, cognizant of so much—indecision, uncertainty, falls from grace, and of course chance.

Wind Whips the Arrows attempts to freeze the wind, presenting gusts, arrows and leaves in neon glass; illuminated, yet frozen. Wind and its detritus, the element that is always in motion for if not it ceases to exist, has been solidified. The attempt to break from the surge of chronological time, and hold dear the psychological, is at work here. If only we could freeze a moment—or stop the wind, which so often is destructive and inconvenient. Aesthetically, one is reminded of Disney—specifically the stylistic nature of earth’s elements in early animation, akin to the dancing metronome of Fantasia (1940). The wind, arrows and leaves, glowing and illuminated in bright yellow neon take on this notion through the indication of movement alone.

69

lightjet print 240 x 160 cm Edition of 3 plus 2 artist's proofs

Darren Sylvester Star Machine, 2023

lightjet print 160 x 120 cm Edition of 3 plus 2 artist's proofs

Darren Sylvester Made up in the Vanity #1, 2023

in the

lightjet print 160 x 120 cm Edition of 3 plus 2 artist's proofs

Darren Sylvester Made up

Vanity #2, 2023

At Disneyland there is an attraction called The Snow White Grotto, which hosts a prominent wishing well. Walt Disney states that, ‘Wishing has long been a favourite subject of mine. Wishes have come true for many of the characters in my motion pictures… and for me, too. A wish is really the first step in the realisation of a dream or goal. Down through the ages, people have used different symbols to wish for things. Sometimes they looked at the stars, and other times the symbol was something else—very often wishing wells.’

The final work in 2 Telegenic 2 Die, Wishes in the Wells, is a photographic depiction of a specially constructed well. Wells appear made to almost be fallen down into, and the space whilst falling, the ‘place’ of the well, is a non-place, simply nowhere; again, relating to the notion of ‘limbo’ as per other works in this exhibition. As Disney so fervently relates, wells are also a place of hope and wishes, a site of longing and optimism. The fact the well itself is but a construction, almost a fallacy, makes the image presented here seem all the more magical, and the artist seem all the more an Engineer, a spinner of tales, a trickster.

Through photography, construction—and arguably a little bit of magic, Sylvester spins a tale larger than himself, larger than the physical works, entering us into the realm of dreams and stars.

FEB/MAR 2023

Darren Sylvester Wind Whips the Arrows , 2022 (detail) eighteen parts, neon, transformers, dimensions variable Edition of 1 in 3 parts, edition 1AP of complete set

“The artist seem all the more an Engineer, a spinner of tales, a trickster.”

DARREN SYLVESTER, 2 TELEGENIC 2 DIE, 23 MAR – 22 APRIL 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Photo: Darren Sylvester

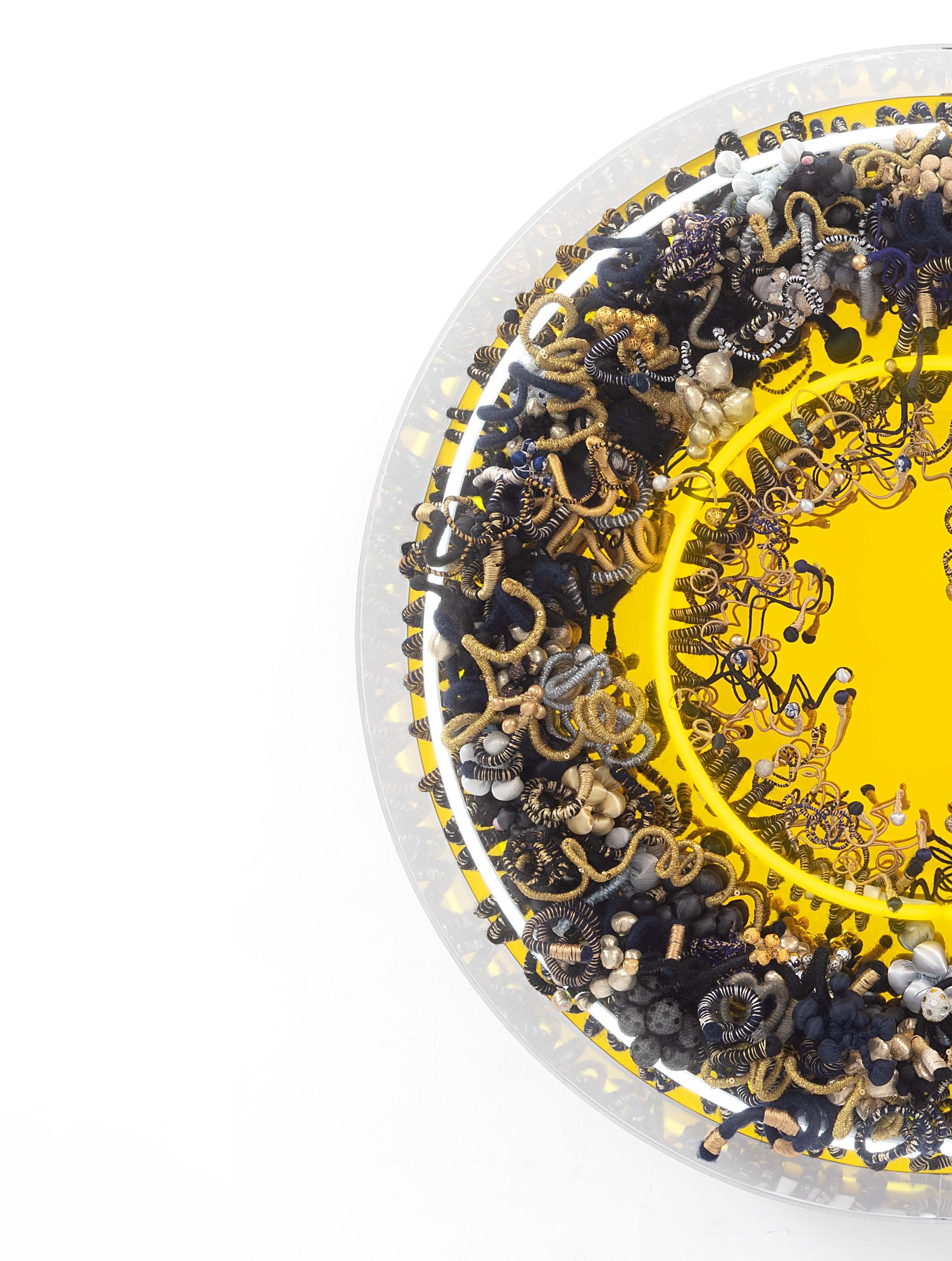

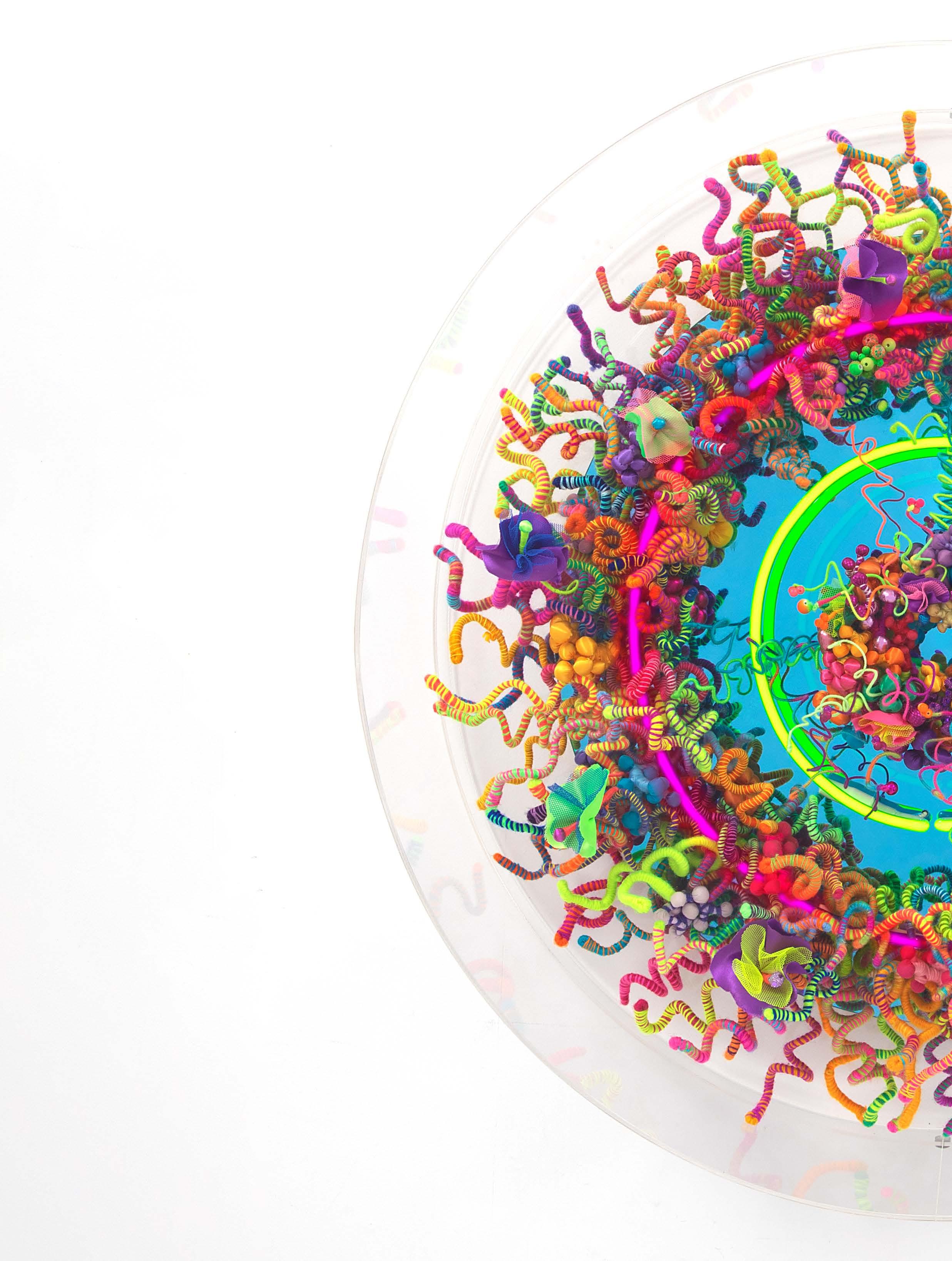

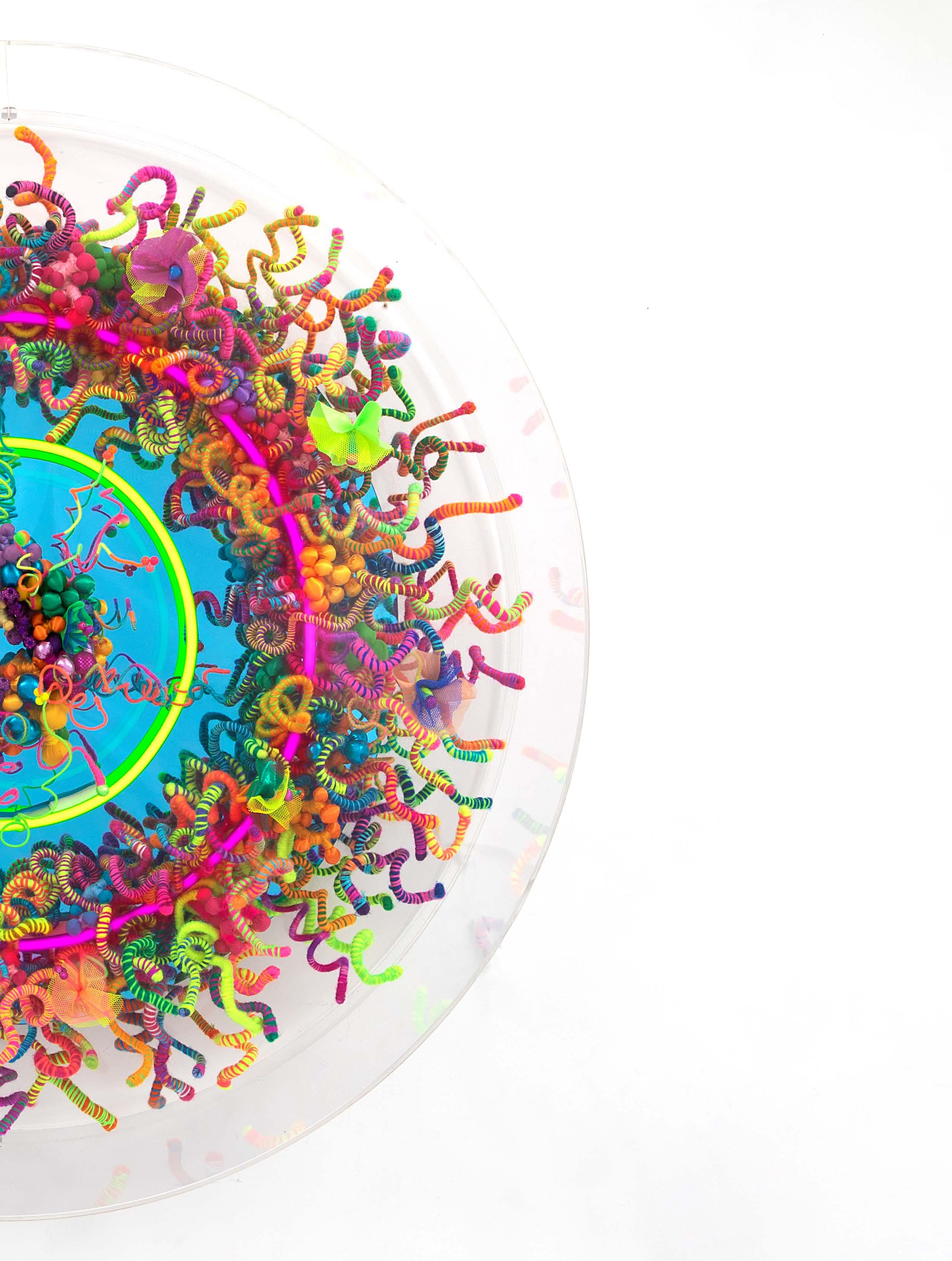

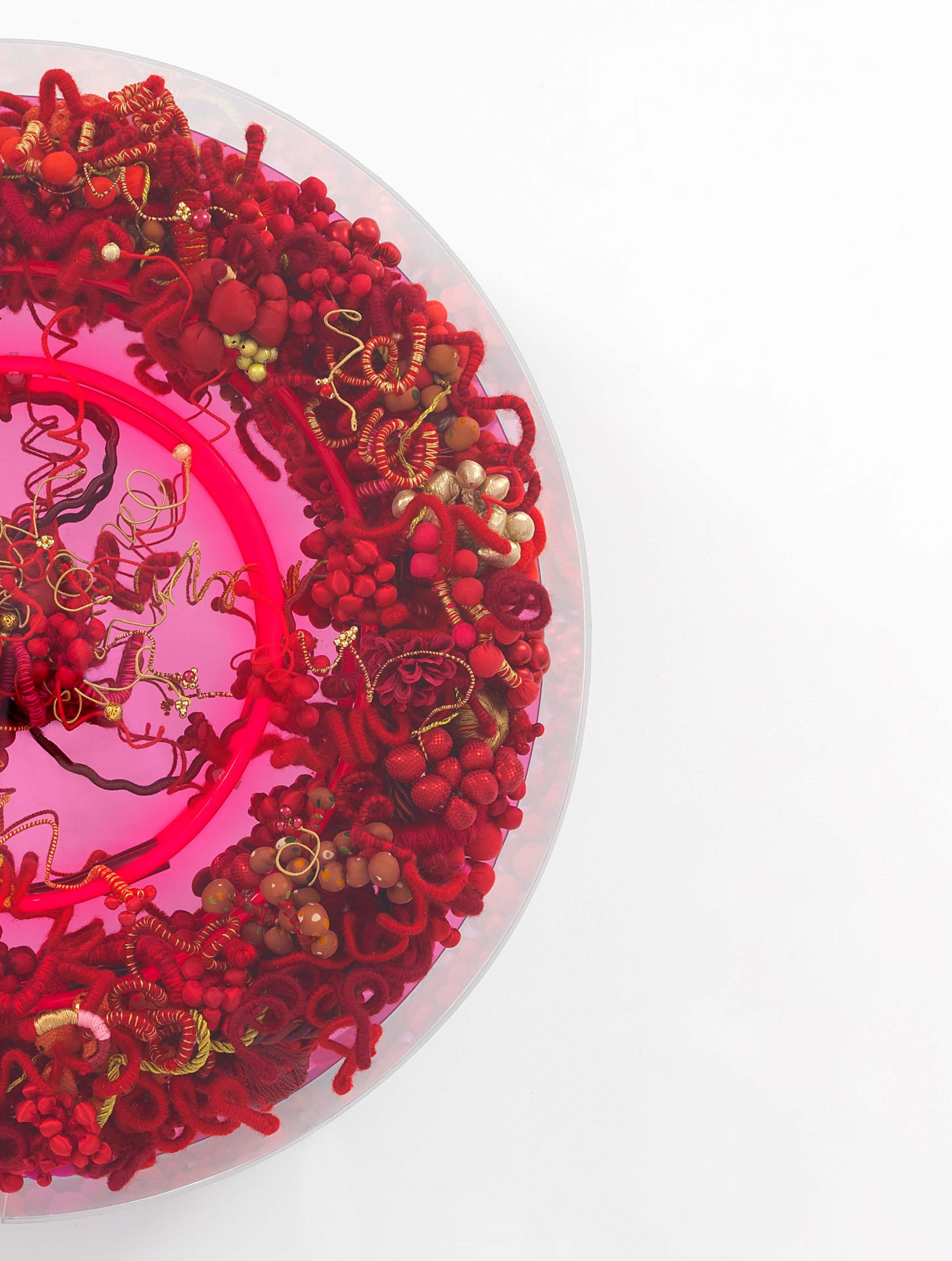

Hiromi Tango: Hanamida 花涙

(Flower Tears)

Art is not created in a vacuum, it can be a statement about society, an expression of autobiographical material, a political commentary; the work of the artist is tethered to time and place but transcends culture and language.

By Dr Patricia Jungfer

FEB/MAR 2023

HIROMI TANGO, HANAMIDA 花涙 (FLOWER TEARS), 23 FEB – 18 MAR 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Edition of 3 plus 2

proofs

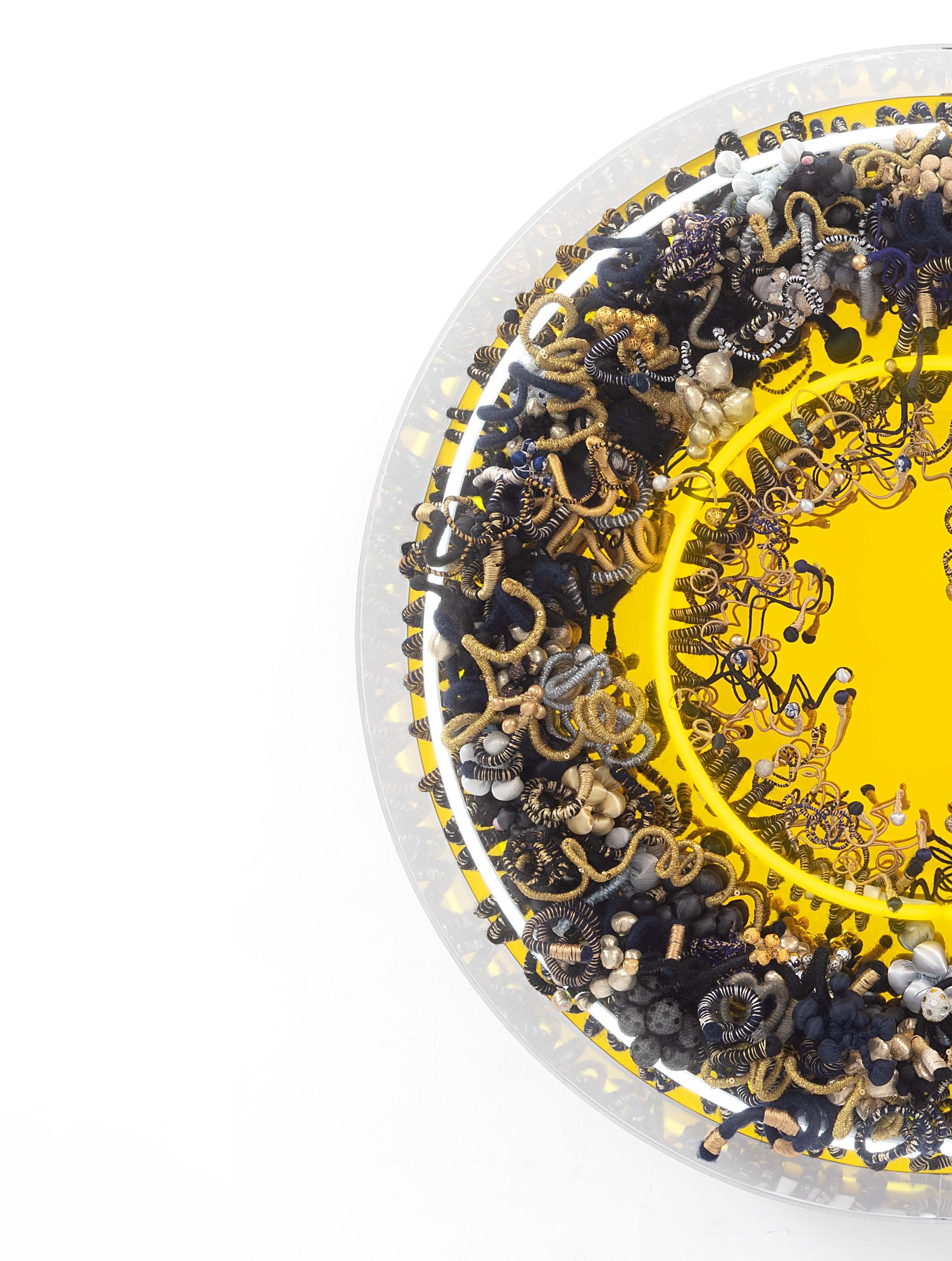

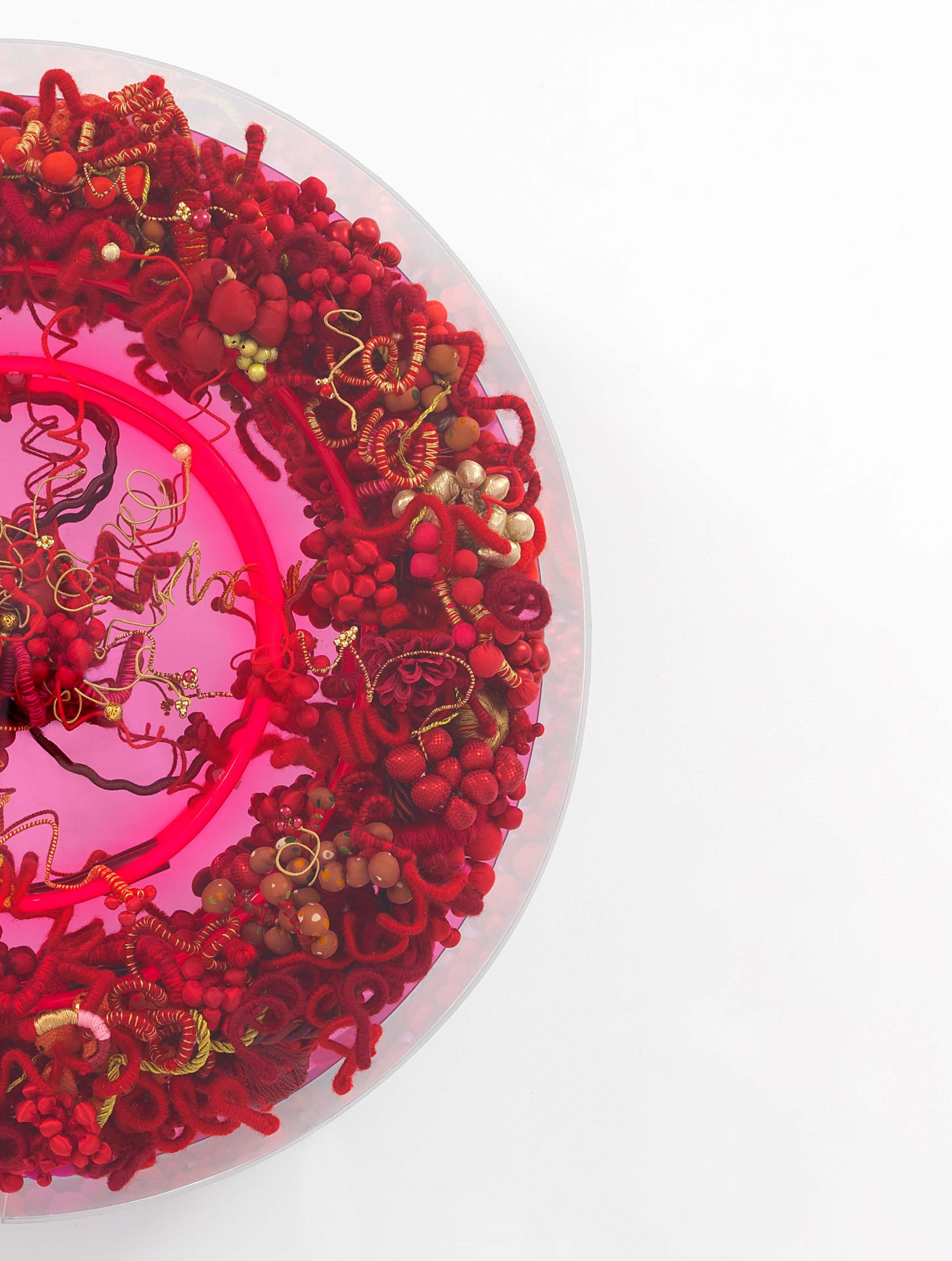

Hiromi Tango Kokurui 黒涙の川 (River of Deep Tears), 2023

artist’s

FEB/MAR 2023

Hiromi Tango

Tsuki no Miyako 月の都 (The Palace of the Moon), 2023

neon and mirrored perspex

55 x 55 x 11.5 cm

Edition of 3 plus 2 artist’s proofs

The exhibition Hanamida 花涙 (Flower Tears) is Hiromi Tango’s way of processing of her feelings, thoughts and emotions that are probably universal and likely to have been experienced by us all in recent years. A sickly withering plant with an exudate was the seed that led to the blossoming of this show. The orchid in her home was a treasure plant, a connection with her homeland and family. The white exudate was for Hiromi like the plant was crying, expressing the distress at its illness and a mirroring of the personal and universal distress.

Over the past three years, individuals and society at large have experienced multiple losses. In Australian communities there have been the losses associated with the bushfires of 2019-2020. These losses were not limited to property, they extended to life and our country’s biodiversity. Shortly after this the COVID pandemic resulted in loss of health, life, job security and community connections. On an individual level there is unlikely to be a single person who has not experienced some form of loss, and in many cases multiple losses, as a result of the pandemic. The impact of the pandemic was attenuated in 2021 and 2022 in Australia with multiple flood events, in some communities the floods exacerbated losses that arose in the bushfires. For Hiromi who lives in the far north of New South Wales and continues to have family ties in Japan, the past few years have been challenging with the cataclysmic events impacting directly on her. Although despite these traumas, this show, like a phoenix, rises from the detritus of these events.

Hanamida 花涙 (Flower Tears) continues the artistic practice of Hiromi, which is a response to her personal experiences and at the same time gives us all permission to reflect on our experiences. Throughout her career as an artist, Hiromi has focused on the expression of self and self-experience. Her work reflects the events and emotions in her life and there is a universality of emotions that she experiences. In conversation with Hiromi about her forthcoming show, we reflected on her practice and the impact of uncontrollable natural events on her current show. The work for this show as in others, ranges across several mediums. Her work has often incorporated performance and there is the desire to engage the audience in her work. Hanamida 花涙 (Flower Tears) incorporates her unique sculptures, oil painting, drawing and photography. Each work is linked to past works, retaining the use of dimensionality, and is shaped by her training in calligraphy. Hiromi hopes with this body of work that she has provided an opportunity for others to share the common and personal emotions expressed in the works and experience a healing after the past few tumultuous years.

“The past few years have been challenging with the cataclysmic events impacting directly on her. Although despite these traumas, this show, like a phoenix, rises from the detritus of these events.”

77

Many moons have passed Beloved faces remain My heart's memory

No words to express Sadness deep inside of me Heavy like a stone

Gently wash away this weight Lightening my heart

Haiku Poems by Hiromi Tango

Hiromi Tango

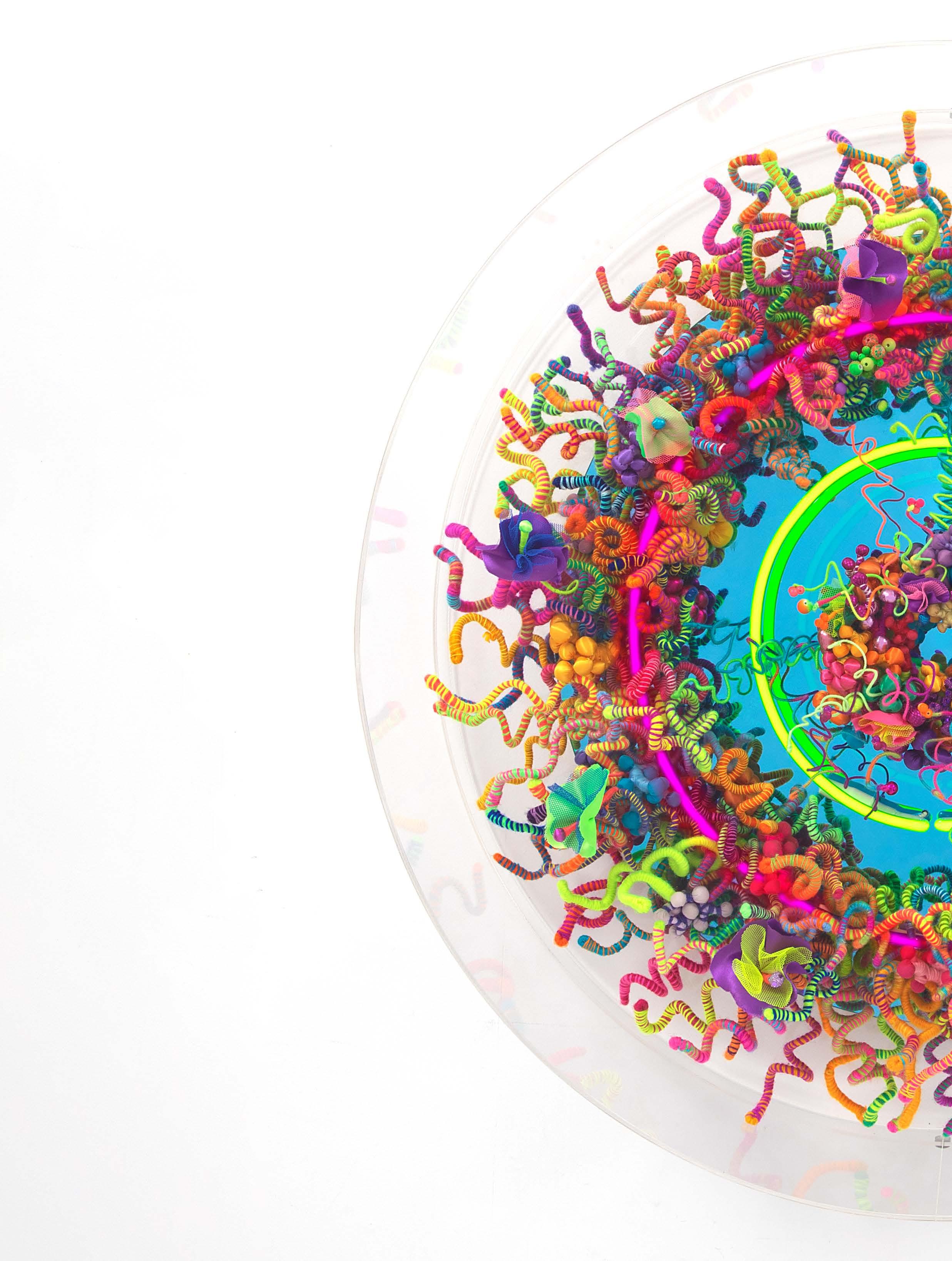

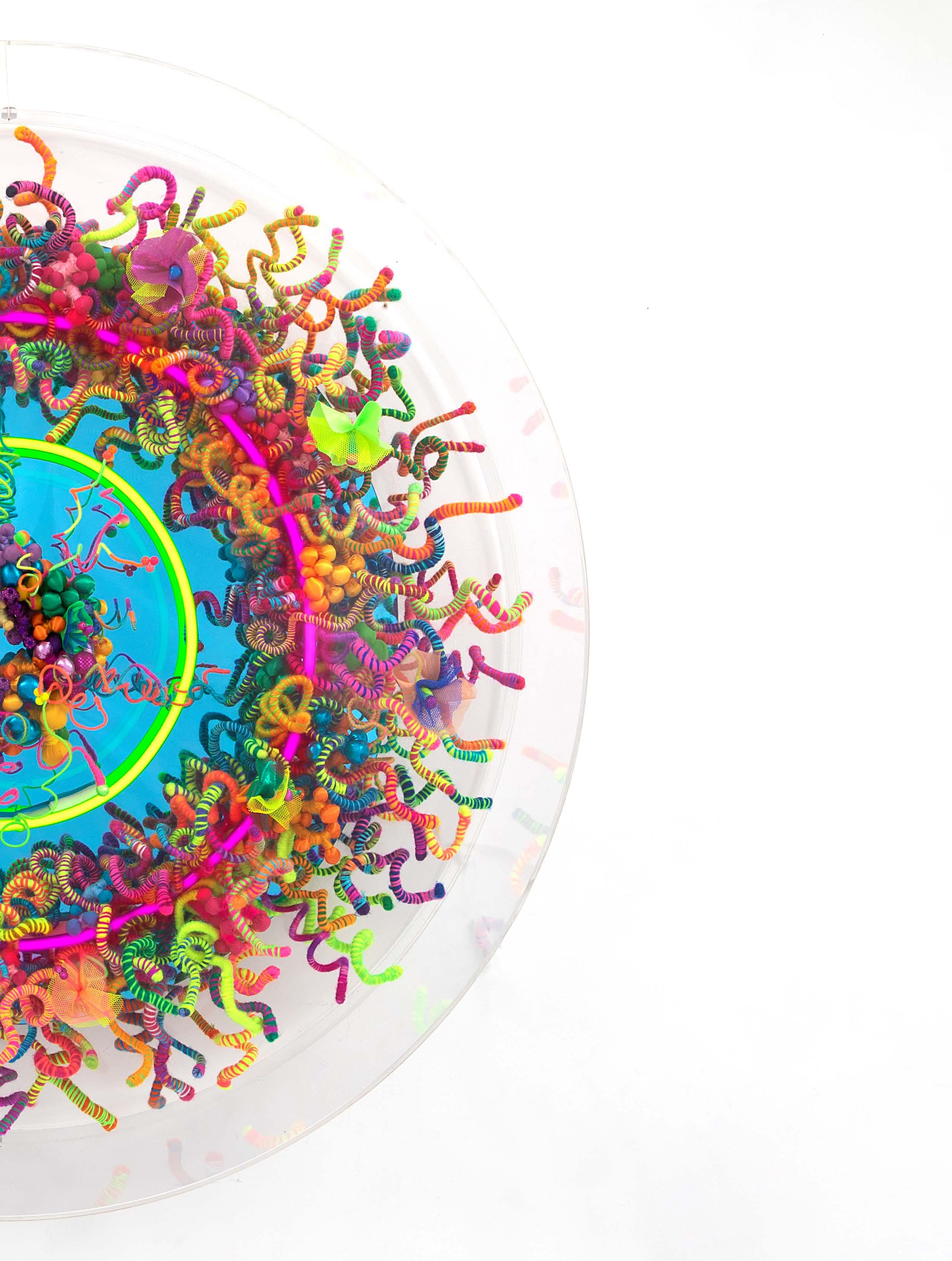

Hanatsukiyo 花月夜 (Flower Moon’s Grief), 2023 neon, woven textile and mirrored perspex 60 x 60 x 14 cm

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Hiromi Tango

Yuka 癒花 (Healing Flower), 2023 neon, woven textile and mirrored perspex 79 x 79 x 20 cm

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Hiromi Tango

Yuka 癒花 (Healing Flower), 2023 neon, woven textile and mirrored perspex 79 x 79 x 20 cm

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Hiromi Tango

Kashin 花心 (Flower Heart), 2023 neon, woven textile and mirrored perspex 60 x 60 x 14 cm

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Hiromi Tango

Kashin 花心 (Flower Heart), 2023 neon, woven textile and mirrored perspex 60 x 60 x 14 cm

Photo: Aaron Anderson

Hiromi has always enjoyed tending her garden, and plants have a special meaning for her; there is a healing component of working in her garden. She memorialises those that have been lost in her life with special and precious plants, tending these plants extends her ability to tend and treasure those that have gone from this world but remain in her heart. In 2022 an orchid—associated with a grandmother who recently died—became wilted and infected with white insects. The plant, to Hiromi, seemed to be crying, and its flowers and leaves wilted. Flowers and plants have symbolic meaning in all societies, at times the same flowers can mean different things to different communities, but the common theme in societies is the use of the flower as a metaphor for emotions that can be difficult to express. A painting in this exhibition of Shiragiku Hi no Tori 白菊火の鳥 (White Chrysanthemums Firebird) connects us to the artist’s Japanese culture, where the flower is used to reflect sympathy and remembrance in mourning rituals.

Hiromi has used this show to work through many of the emotions she has experienced over these past few years, mourning the loss of artworks in the floods and of beloved family members in Japan. The darkness of these losses is captured in her photographic work Hagoromo Hi no Tori 羽衣 火の鳥 (The Feather Mantle Firebird). In the images, Hiromi documents a performance where she is covering herself in black paint. While the works are on one level heavy and melancholy, the light of the vessel she is holding creates an illusion of the Firebird, suggesting that even in the depths of grief there can be hope. There are references in the images to her culture and it is a documentation of a personal mourning ritual. The wearing of a Kimono is especially poignant as her grandmothers were makers of kimonos. The fragility and transience of life is represented by the flowers that encircle her, the black paint covers her like the sorrow that can drown us when loss feels raw and overwhelming.

From the age of seven, the artist studied calligraphy with recognised Calligraphy Master Oda Sisei 織田子青 ,who passed away when Hiromi turned eighteen. Calligraphy is a visual art related to writing, hours will be spent practicing the letters which can be a meditative process for the person practicing the art. Specialised brushes, papers and inks result in a distinct mark making. Hiromi would make her own ink for her works, manipulating the inks viscosity for artistic effect. The images were produced with distinct gestures and movement. In this exhibition, Hiromi uses oils rather than inks and the calligraphic origin of her art asserts itself in the paintings, drawings and in her sculptures.

For Shiragiku Hi no Tori 白菊 火の鳥 (White Chrysanthemums Firebird), Hiromi has applied oils so that the image appears to be an abstract image. The sweeping gestures are derived from calligraphy and the incorporation of words written in calligraphy; her early training rebirthed in an alternative form. Hiromi continues her use of calligraphy to produce her work and draws on a myth that is well known in all cultures: the myth of the magical bird that can rise from the ashes, the Phoenix. In Western societies, the phoenix was popularised in the late twentieth and early twenty first century by JK Rowling in her Harry Potter series. In Japan the Phoenix is the firebird, and Hiromi recalls as a child reading Tezuka, and his manga series Bird of Fire Hi no Tori 火の鳥. Tezuka is most known for his Manga series Astro Boy, Bird of Fire was not completed before his death and has not reached the popularity of Astro Boy. Bird of Fire is about immortality and Hiromi’s painting of the Firebird is a reminder to her, and the audience, that even in death there is something that remains which is not lost; even if it just a memory.

As Hiromi and I spoke about what influenced this exhibition, it became evident that Hiromi is like the plant that has been grafted, the root stock remains Japanese, the scion what we see, a hardy strong Australian woman. Being in Australia has enabled her to loosen the constraints of Japanese culture and yet take strength to grow and produce very powerful work—which is often why we use grafted plants. The works in this show are delicate and beautiful, yet they are very strong. Hiromi has been very strong in the past year as she has struggled with Long Covid and loss, and she hopes that her strength as expressed through her art can give everyone else the strength to feel some of the emotions we have all had to deal with during a tumultuous few years.

FEB/MAR 2023

“She memorialises those that have been lost in her life with special and precious plants, tending these plants extends her ability to tend and treasure those that have gone from this world but remain in her heart.”

HIROMI TANGO, HANAMIDA 花涙 (FLOWER TEARS), 23 FEB – 18 MAR 2023, S+S SYDNEY + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW

Hiromi Tango Kogiku 踊菊 (Chrysanthemum Dance), 2023 (detail) Edition of 3 plus 2 artist’s proofs

Hiromi Tango Kogiku 踊菊 (Chrysanthemum Dance), 2023 (detail) Edition of 3 plus 2 artist’s proofs

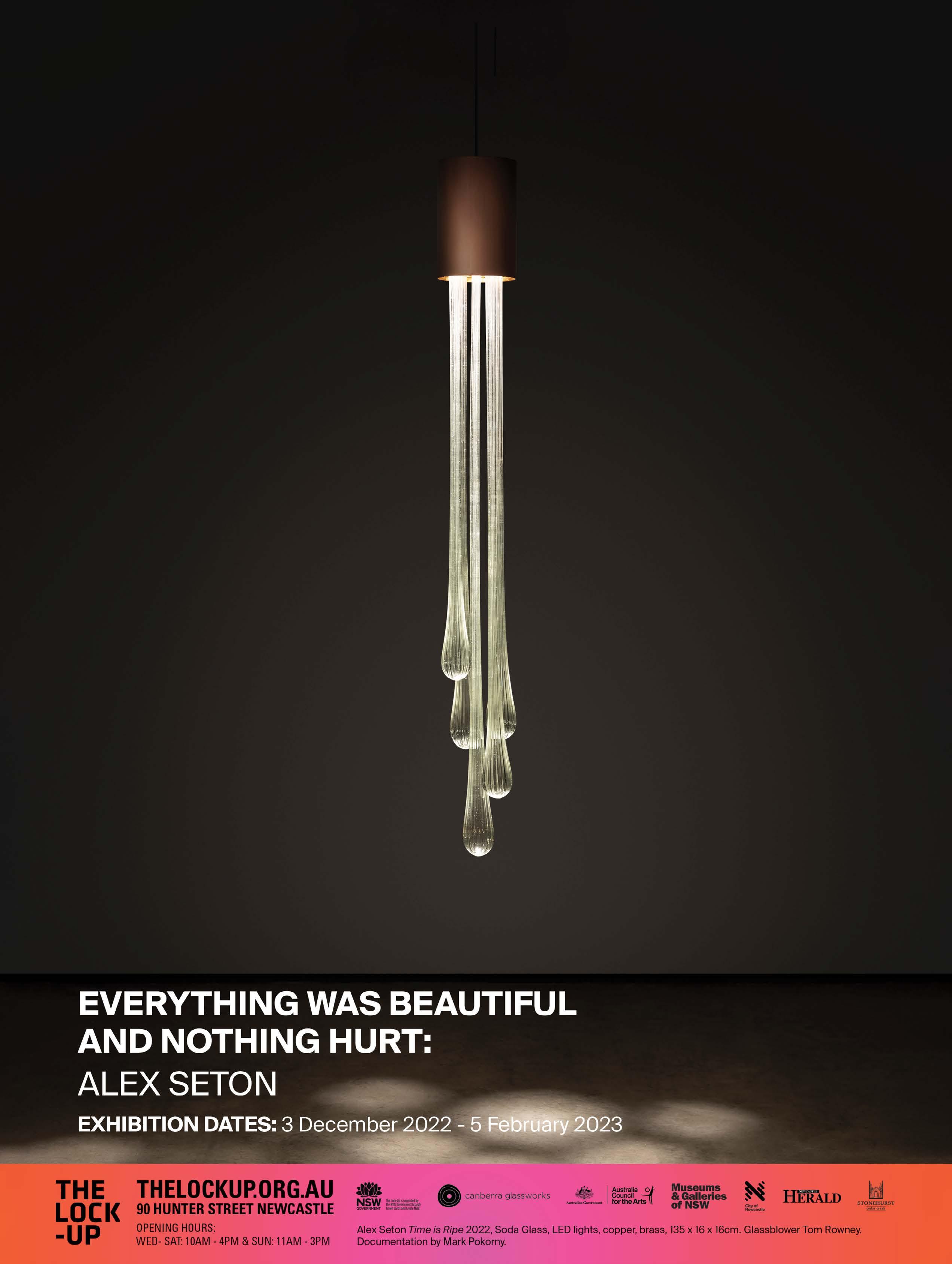

Alex Seton: Everything was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt

Alex Seton has carved his career in marble. Making a whole new body of work in glass for the first time, it’s hard to imagine him contending with a more contrary medium.

By Leigh Robb

FEB/MAR 2023

Alex Seton with his works in progress at Canberra Glassworks, 2022.

ALEX SETON, EVERYTHING WAS BEAUTIFUL AND NOTHING HURT, 7 DEC 2022 – 5 FEB 2023, THE LOCK-UP, NEWCASTLE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO FIND OUT MORE

Photo: Brooke McEachern

FEB/MAR 2023

Installation View: Alex Seton The Amber of this Moment, 2022. The Lock-Up, Newcastle

Photo: Mark Pokorny

Faster than light travel, as science fiction authors routinely remind us, has the capacity to warp time, depositing hapless cosmonauts in various dislocated futures and alternate presents. In Alex Seton’s exhibition at The Lock-Up, Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt, the light shed by luxurious modernist chandeliers leaves the audience unfixed in time and uncertain of location. The objects’ pendulous light evokes streaks of tracer fire and a downpour of bombs, but hung at eye level, the dense arrangements of glass tubes also take on a bodily presence, resembling jellyfish-like aliens, whose translucent, glowing forms distort the perception of space. This beautiful and beguiling exhibition has grown out of intense material discovery and is deeply informed by the artist’s historical research, yet it warps and jumbles time.

The title of Seton’s solo exhibition is borrowed from Kurt Vonnegut’s famous semi-autobiographical anti-war science fiction novel, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). While a prisoner of war in a German abattoir, Vonnegut survived the fire-bombing of Dresden; he then spent two decades struggling to make sense of his experience. The resulting novel juxtaposes mordant humour, time travel and alien abductions with the horrors and banalities of the Second World War. When conceiving of his exhibition, Seton recalled re-reading Vonnegut’s book during lockdown; the titular line is the wishful epitaph that the central timetravelling optometrist, Billy Pilgrim, imagined being carved onto his tombstone.

Similarly, Seton’s exhibition illuminates the ambiguous coincidences that collide the horrors of war and artistic creation. In researching Newcastle’s Leonora Glassworks, Seton uncovered the stories of the business’ founders, Joe Vecera, Henry Vecera and Joe Trvdik, three Czechoslovakian master glass blowers who immigrated to Australia in 1936. When the Second World War broke out, they were employed at the ELMA (Electric Lamp Manufactures Australia) lampworks in Newcastle, their skills hijacked to create ‘bombsights’, precision glass devices used on military planes to accurately aim and deploy bombs.1 In 1947, the trio established the Leonora Glassworks in a coal shed which was once part of the Old

Lambton coalmine, and in the 1960s and 70s, this business went on to design stunningly sophisticated modernist chandeliers for Anzac Clubs, RSL halls and civic centres for surviving soldiers.2 Around the same time that the war veteran social clubs were being decommissioned in the 1980s and 90s, the Leonora Glassworks also closed its doors.3

Time travel narratives tempt their readers with the hope of redeeming history, the capacity to reorder events according to a gentler logic than mere causality. But with his fatalistic refrain, ‘so it goes,’ Vonnegut depicts history as inescapable, arguing that the present cannot supplant the past. In his novel, The Tralfamadorians, an alien civilisation who abduct Billy Pilgrim, have no perception of time: ‘There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What [they] love in [their] books are the depths of many marvellous moments seen all at one time’.4 In the chandeliers of the Leonora glass blowers, Seton can’t help but see tallboy missiles, raining cluster bombs, and lethal droplets. So it goes.

1 Greg Ray, Newcastle’s Leonora Glassworks, 26 June, 2019. https://www.phototimetunnel.com/newcastles-leonora-glassworks. Accessed 10 October, 2022.

89

2 During the 1960s and 70’s Leonora Glassworks made large-scale chandeliers and luminaires were designed with architects for the buildings including the North Sydney Anzac Memorial, Camberwell Civic Centre, Dubbo Civic Centre, Blacktown Shopping Centre, Australia New Zealand Bank Head Office, Sydney, and the Menzies Hotel Bar.

3 The Leonora Glassworks closed its doors for the last time in 1982.

4 Kurt Vonnegut Jr, Slaughterhouse-Five, 1969, Vintage, London, 2000, p.72.

“There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What [they] love in [their] books are the depths of many marvellous moments seen all at one time.”

Installation View: Alex Seton Everything was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt, 2022.

The Lock-Up, Newcastle

Photo: Mark Pokorny

Installation View: Alex Seton Everything was Beautiful, and Nothing Hurt, 2022.

The Lock-Up, Newcastle

Photo: Mark Pokorny

Seton has carved his career in marble. Over the past twenty years, he has shaped stone to create stunning simulacra: folds of fabric enveloping a body for a sea burial; a crumpled pillowcase; or a damp towel thrown over a railing. Seton demonstrates anatomical verisimilitude in the creased soles of feet, the cartilage of the ear, or a human skull. His sense of history is evident; marble pulls toward the memorial, as he commemorates the everyday by capturing the trace of the absent body or the memory of those now departed.

Making a whole new body of work in glass for the first time, it’s hard to imagine the artist contending with a more contrary medium. One process is subtractive, the other additive. Using fire and breath to inflate a rod of molten glass into a hollow blown form versus employing the cool steel of a point chisel and the force of a hammer to fashion stone. But Seton was ably guided by master glassblowers Tom Rowney, Annette Blair and Katie Ann-Houghton during a residency at Canberra Glassworks.

FEB/MAR 2023

“Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt”

- Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, 1969

93

Installation View: Alex Seton Many Marvellous Moments Seen all at One Time, 2022. The Lock-Up, Newcastle

Photo: Mark Pokorny

Installation View: Alex Seton Unstuck in Time, 2022.

The Lock-Up, Newcastle

Photo: Mark Pokorny

Installation View: Alex Seton Unstuck in Time, 2022.

The Lock-Up, Newcastle

Photo: Mark Pokorny

The nine extraordinary new glass sculptures Seton has produced for The Lock-Up perform a type of time travel, summoning modernist ghosts. Each piece explicitly references a chandelier created by the Leonora Glassworks, though Seton’s research has revealed that none of the original pieces are still extant. The centrepiece of the exhibition, Trying to Reinvent Themselves and Their Universe, which illuminates the main gallery, is an homage to the chandeliers of the Australia New Zealand Bank Head Office in Sydney. The five alien lights appear to hover throughout the long, darkened space. From each copper fitting, eleven striated glass droplets cascade. The incongruous, anachronistic surrounds of The Lock-Up, originally the holding cells of a nineteenth century police station, remind us of Vonnegut’s prisoner of war camps. In the work Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt, installed in the Yard, 109 amber and clear diamond-point moulded glass pieces hover like a cloud above marble fragments, evoking ruined European capitals, prostrate beneath a shower of bombs.

In Cell F, The Amber of this Moment is a tribute to a piece Leonora Glassworks made for the North Sydney Anzac Memorial Club in the late 1960s. These forty-eight hollow droplets describe a volume of air, capturing a collection of suspended breaths. Working in glass has given Seton licence to move away from the figurative, but the impulse to memorialise remains. Rather than the trace of the body hewn from stone, vanished exhalations are remembered in glass.

Seton’s sensibility could be described at Vonnegutian: staunchly anti-war and trying to find a way to reflect on its horror and absurdity without glorifying it. The same techniques and materials that were used to build bombsights are now employed to fashion new glass chandeliers whose pendulous forms echo the shape of missiles, the jagged burst of light of an exploding bomb, or the drop of a heavy tear. These works are a tribute to the Leonora glassblowers and to a community disaffected by war, but they do not elide history in their memorialisation. As Vonnegut writes in SlaughterhouseFive ‘there is nothing intelligent to say about massacre’.5 Where there are no words to make sense of the tragedy of war, could there be light and shadow to hold a space to remember? Seton has harnessed fire to create objects of enduring light.

95

5 Kurt Vonnegut Jr, Slaughterhouse-Five, 1969, Vintage, London, 2000, p.16.

ALEX SETON, EVERYTHING WAS BEAUTIFUL AND NOTHING HURT, 7 DEC 2022 – 5 FEB 2023, THE LOCK-UP, NEWCASTLE + EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO FIND OUT MORE

Yang Yongliang: Vanishing Landscape

For Singapore Art Week 2023, Yang Yongliang presented a mesmerising collection of works in his solo show Vanishing Landscape at the Gillman Barracks. Breaking with his previously monochromic palette, the exhibition harnesses imagined scenes of verdant cliffs and cascading bodies of water that transform into sprawling hills humming with urban life. Through their artificialness, the works navigate universal themes of our everchanging landscapes and the contemporary issues that they face.

By Clara Che Wei Peh

97

YANG YONGLIANG, VANISHING LANDSCAPE, 7 – 15 JAN 2023, BLOCK 43, GILLMAN BARRACKS 43 MALAN ROAD 01-17, S+S SINGAPORE + TO SEE AVAILABLE WORKS BY YANG YONGLIANG ACCESS THE VIEWING ROOM BY ENTERING YOUR EMAIL ADDRESS bit.ly/yangyong

Singe-Channel 4K Video (8 Minutes) Watch Online: https://vimeo.com/785518927

Yang Yongliang The Lakes, 2022 (video still)

Yang Yongliang modelled his videos and lightboxes closely after the traditional shanshui paintings through a monochromatic lens in his earlier practice. In his more recent works, Yang expands the universes he creates to encapsulate colour, while also shifting the focus on artificial landscapes onto urban lives and individual narratives. Vanishing Landscape, the solo presentation of his work held by Sullivan+Strumpf during Singapore Art Week 2023, is an illustration of these new directions.

Trained in ink-wash painting and calligraphy himself, he takes photographs and videos captured across different cities he resides in and travels to, and seamlessly layers them into virtual environments that take after the painting tradition. Throughout ancient China, the cultural significance of landscape paintings has evolved through time, with the genre embodying man’s desire to withdraw into the natural world at the end of the Tang dynasty, becoming a virtue signaling exercise for scholars in Song dynasty, and further (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2004). Despite its various transformations, it is noted that the Chinese landscape depictions of nature are ‘seldom mere representations of the external world’ but are ‘expressions of the mind and heart of the individual artists’ (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2004).

Born in 1980 in Old Town Jiading, Shanghai, Yang witnessed the rapid and ever-expanding growth of China’s mega-cities and the endless cycle of demolition and reconstruction that follows, lending towards his surreal and almost dystopic blending of the natural landscape with manmade constructions. Shanshui paintings generally bear little resemblance to the ‘real’ visible nature but are more of abstractions and imaginations. Yang’s landscapes are simultaneously more ‘real’—in that he takes from photographs and footages captured from lived cities and environments, and less likely, as he pushes the limits on how urbanisation can take over nature.

“Yang’s landscapes are simultaneously more ‘real’—in that he takes from photographs and footages captured from lived cities and environments, and less likely, as he pushes the limits on how urbanisation can take over nature.”